Jun 1, 2024

Medfield is in full bloom once again, as we welcome the month of June. Along with my usual time-travel musings, I’ve been thinking about Juneteenth, wondering about Medfield’s involvement in the antislavery movement. Evidence shows that Medfielders were active in the movement, which gained strength in the northern states during the 1830s. In bits and pieces, the story is here in our archives, waiting to be told. So far, I have uncovered antislavery connections among the Medfield Library and the Medfield Lyceum.

Anti-slavery Activity Proposed in 1832 by Medfield Lyceum

As I wrote in March, the Medfield Lyceum’s “editresses” published the Lyceum Gazette newspaper in 1861-1862. Since then, I have learned (without surprise) that the Medfield Lyceum was originally established by prominent Medfield men whose names are familiar to those who study the town’s history (Onion, Allen, Leland, etc.) in 1832. The men met in the space over Noah Fiske’s store. In 1831, the New England Antislavery Society (NEAS) “the first antislavery association among white activists to demand immediate, unconditional abolition of slavery and equal rights for black Americans, without compensation to the slave-owners and without colonization (forced expatriation) of the freed slaves” (Roberts) had been founded in Massachusetts by William Lloyd Garrison.

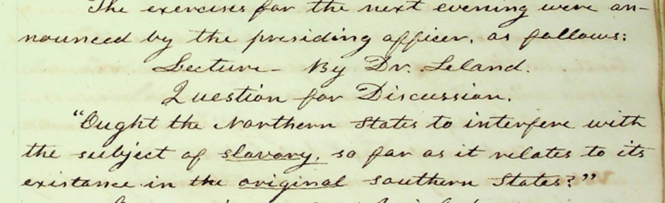

By 1835, branches of the NEAS had begun in every New England state, so the NEAS itself became known as the Massachusetts Antislavery Society. Medfield shared the growing antislavery passion among the northern states, although I still need to find more information on the specific activities of Medfield’s antislavery movement. The “Secretary’s Book” of the Medfield Lyceum, which we possess, recorded the topics of the group’s lectures and discussions. Among the first questions debated were “Were our ancestors justified in taking possession of Indian lands?,” “Whether Death ought ever to be inflicted as a punishment?” and on April 6, 1832, “Ought the Northern States to interfere with the subject of slavery, so far as it relates to its existence in the original southern states?”

The discussion itself, unfortunately, was not recorded.

Books from the “Medfield Anti-Slavery Library Association”

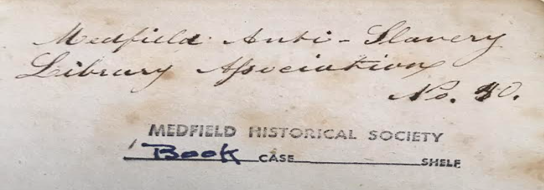

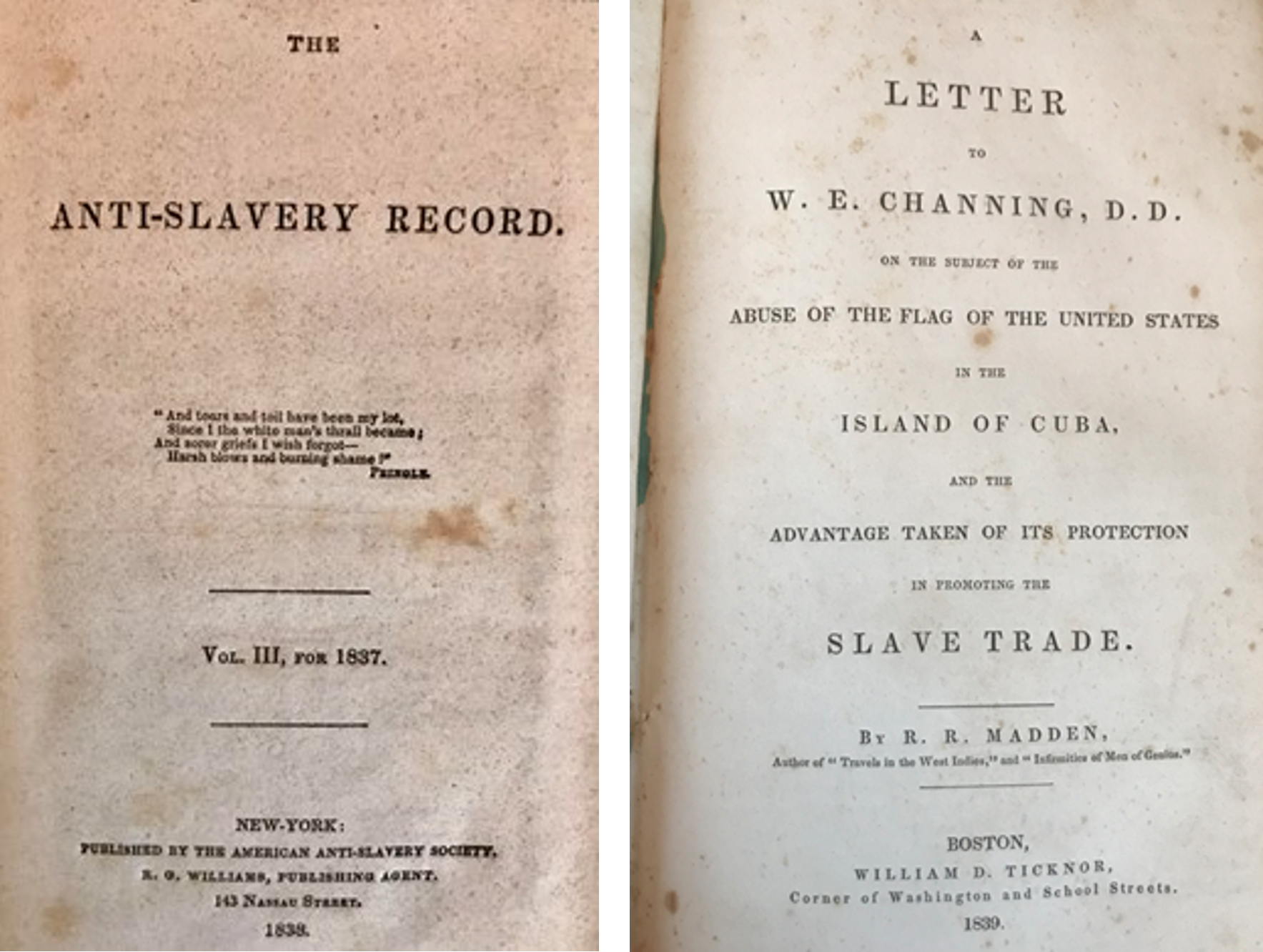

Other evidence of Medfield’s antislavery movement exists in the form of two books from the 1830’s that were donated at some point to the Medfield Historical Society. These two books are marked as belonging to the “Medfield Anti-Slavery Library Association.” One is Volume 3 of The Anti-Slavery Record. The other is William Ellery Channing’s Letter on the Subject of Abuse of the Flag of the United States in the Island of Cuba and the Advantage Taken of Its Protection in Promoting the Slave Trade. These books can be made available for guests to view when they visit.

What was the Medfield Antislavery Library Association? We are only just beginning to find out. To date, I have found no direct information about this group. These books were published during the age of the “social library,” a subscription library system invented by Benjamin Franklin that was replaced by the free circulating libraries we know today. Patrons who were involved in the antislavery movement would have paid dues for the purchase of books and the privilege of reading and discussing them. Discussion was a key component of the social library model.

Years ago, I heard that a rare manuscript of some sort was “discovered” in one of Yale University’s libraries. How on earth, I thought, could a library not even know what it contains? Since I’ve been volunteering at the Medfield Historical Society and Museum, which has a lot in common with a library, I can understand easily. It is only through the efforts of volunteers, year after year, decade after decade, that we are able to provide the services we do. We would like nothing better than to be able to tell the public exactly what we have, where it is located, and where we got it. We have “discovered” some phenomenally exciting artifacts from the nearly 300 year-old story of Medfield, objects that excited dedicated volunteers of the past, who never intended to make them challenging for us to find. If only they had had the technology to create sustainable information systems to serve the town. With all the archival and technical resources available today, we should be able to do just that: tell the never-ending story of our wonderful town for future generations. With continued support, we will stay on the job.

Works Cited

Roberts, Timothy M. “New England Antislavery Society.” Dictionary of American History, edited by Stanley I. Kutler, 3rd ed., vol. 6, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003, p. 47. Gale In Context: U.S. History.