Mar 1, 2024

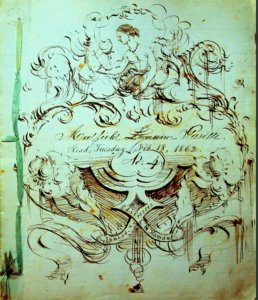

Women’s History Month, 2024: At the coffee shop, I see women with beverages, children, friends, notebooks and folders, and I can’t help but imagine them in a billboard-sized group photo of all the Medfield women who have kept this town going for over 300 years. As a volunteer in Medfield’s archives, I know the thrill of finding a treasure, and for this month I have something special. I will focus this article on the first of two (and there may be more) hand-written and illustrated newspapers called the Medfield Lyceum Gazette, created in 1862 by the women of the Medfield Lyceum. Its stated purpose is dedication to art, literature and politics. This issue is No. 4; its cover states “read Tuesday, February 18, 1862”. I am especially thrilled with my discovery because, as a college student and later a teacher, I concentrated on 19th-Century American literature and history.

The Lyceum movement, named for Aristotle’s famous school in ancient Greece, began in New England in the early 1800s and spread to the midwest, sparking widespread enthusiasm for adult education, training, and learning of all kinds. By the mid-1800s, people were flocking to classes, lectures, authors’ appearances, and myriad venues of learning. At the same time, antebellum America was abuzz with the electricity of Transcendental thought, abolition of slavery and reaction to the Fugitive Slave Act, women’s rights and suffrage movements, social and industrial reform, and the birth of the American novel.

The entire manuscript is handwritten in beautiful cursive on blue paper, now faded, bound through its cover with blue ribbon. The cover design seems to embody the idea of feminine creativity (Figure 1). A key point is that this is not merely the only copy left in existence, but rather it is the only copy ever made; it is one-of-a-kind. The “editresses,” as they called themselves, were E. Inness and M. Hamant. Students of Medfield history may recognize that these are old Medfield surnames, but I have not yet had a chance to research the lives of these women. In fact, I believe that the editors of the publication changed frequently because the first page serves as an apology to anyone whose work was not published due to missing the deadline for submissions, and the editresses state that any work received after the deadline would be passed on to their “successors.”

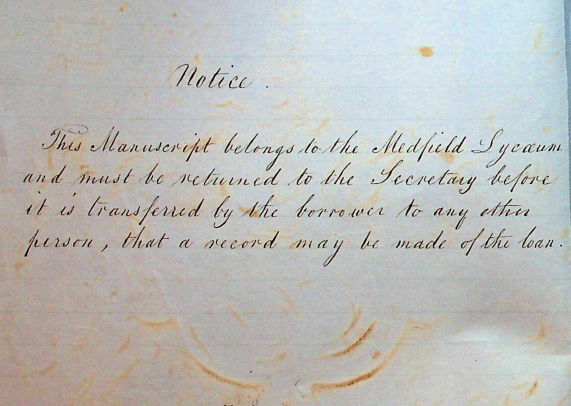

I am trying to understand how the Medfield Lyceum, and its publication, actually worked. From what I can gather of their processes, it looks like the editorial staff would solicit written material from members, and then gather, perhaps monthly, to edit and review submissions, often writing pieces of their own. When they had enough material, they “published,” which meant preparing a single hand-wrought copy. That single copy would then be celebrated as a public event, where it was read and discussed, presumably with light refreshments served. After this public reading, the manuscript was made available for individuals to borrow, with the strict understanding that they must not lend it to anyone else, but return it directly to the Lyceum secretary.

We are in the process of digitizing the Medfield Lyceum Gazette for the MHS web site. The writing is fairly legible, but there is no table of contents or obvious system of organization. For now, I will try to recap two written pieces from Number 4. First, I puzzled over a lengthy, somewhat satirical-sounding letter to the Editresses, which appears to challenge an article published earlier. I only wish I had that earlier article, because it involved the Peak House and supposedly “told the story of the Peak House as the world tells it.” The article was written by the eponymous “Seth Jr.”, and the letter-writer tells us that “aliases was (sic) very common when folks got in bad scrapes.” To increase my frustration, the letter writer refers to a “conflagration” at the Peak House, asserting that the house could not be “a Phoenix,” as it lacked wings.

Following that alarming piece, I deciphered a lovely essay titled “The Gospel Ship,” and was rewarded with goosebumps when I reached the last line. The essay is the reminiscence of a man who recalls an unforgettable person from his childhood, “Uncle Thurber.” The author describes how he and his kid brother, who slept in the same room, used to be fascinated by an old, retired sea captain, “dressed like a celestial voyager,” who frequented the local chapel. The two brothers loved to hear Uncle Thurber’s tales of foreign ports, but they especially loved hearing about a mysterious ship that the old man was continually waiting for; he said The Gospel Ship was moored in the riverbank, just out of sight. The mystical vessel was “lighted with spiritual gas” which made the “gemmed walls blaze with peculiar beauty.” With the faith of children, the author and his brother never doubted that they would see the ship, taste its delightful fruits of gold and silver snow, and see the beautiful birds that nested on its masts. As the tale inevitably concludes, the grown-up author admits that he should have known there was no such ship. The story’s sad last line reads, “my brother now sleeps on the banks of the Pearl, down in Dixie, and I have never seen the clipper Gospel Ship.” When my goosebumps subsided, I opened a browser to look for the Pearl River. During the Civil War, a confederate prison stood on the banks of the Pearl in Jackson, Mississippi. “Almost every day…” according to Harper’s Weekly, “two or three were carried out dead, and sometimes lay at the entrance to the bridge for four days” (Mackowski).

A group of women, some coffee, some notebooks….Happy Women’s History Month, Medfield. You can be sure that you will hear more about the women of the Medfield Lyceum and their newspaper, The Medfield Lyceum Gazette.

—–

Mackowski, Chris. “The Prison over the Pearl River at Jackson, Mississippi, Where Union Prisoners Have Been Confined.” Emerging Civil War, Childress Agency, 2 Jan. 2024.