Feb 1, 2023

On the issue of slavery in America, one usually thinks right away about the Southern States, but as William Tilden reminds us in his “History of Medfield 1650-1886,” that in Medfield’s early history, “slavery was common with most wealthy citizens.”

The earliest slaves in the then Massachusetts Bay Colony were Native Americans, but by the time Medfield was first settled there were 150 Africans living in Massachusetts Bay Colony. The first Africans into Massachusetts came in 1638 when the British ship, the Desire, imported the first several Africans.

By 1740, the number of slaves in Massachusetts Bay colony had increased to over 3,000.

In 1641 Massachusetts Bay passed what were called the Body of Liberties. These laws defined who could be enslaved but did not take away the “natural rights” of enslaved men and women. An important characteristic of slavery in Massachusetts that distinguished it from slavery in the Southern Colonies was in the area of legal rights. Blacks and Native Americans, enslaved or free could, for example, testify in court and initiate lawsuits.

In 1741, Medfield’s First Parish Church voted that infant slaves could receive baptism “if the masters think it their duty, even though their parents not being in covenant.”

By the middle of the 1700s, Boston-based ships would sail to Africa, collect African slaves and deliver their human cargo to the Barbados and other West Indian islands or to southern colonies such as Virginia. In exchange the ships would return to Boston with cargos of wine, salt, sugar and tobacco.

A high percent of the Black new arrivals in Massachusetts during the legal slave trade had been shipped here from the West Indies rather than directly from Africa.

According to the census of 1754, there were more than 900 slaves over the age of 16 in Boston alone. By 1755 the Black population in Massachusetts made up about two percent of the colony’s population. At the same time, Blacks made up about eight percent of Boston’s total population.

The slaves in Massachusetts worked in both the area of farming and livestock in rural area and a variety of occupations in Boston such as bakers, carpenters, blacksmiths, tailors, and printers. A number of Black New Englanders, especially women, also worked in domestic service in families.

We know, for example, that Rev. Joseph Baxter, Medfield’s second minister, owned several slaves.

According to town records, “in 1714 Mr. Baxter’s slave Tony was paid for ringing the church bell.” When Baxter died he left in his will “the service of my Negro slave, Nanny, be given to my wife.”

He added that the slave would become free upon the death of his wife, provided that the slave, Nanny, “behave herself dutifully.”

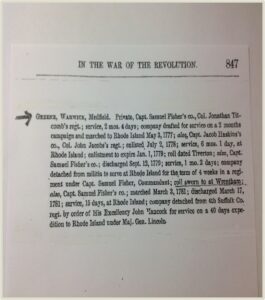

Two Medfield slaves, Warwick Green and Newport Green, were given their freedom and fought during the Revolutionary War. Warwick first went into service on April 27, 1777, under the command of Captain Sabin Mann’s Company of Medfield militia, drafted to serve in the Rhode Island alarm. He later was with the men called to reinforce the Continental Army.

Two Medfield slaves, Warwick Green and Newport Green, were given their freedom and fought during the Revolutionary War. Warwick first went into service on April 27, 1777, under the command of Captain Sabin Mann’s Company of Medfield militia, drafted to serve in the Rhode Island alarm. He later was with the men called to reinforce the Continental Army.

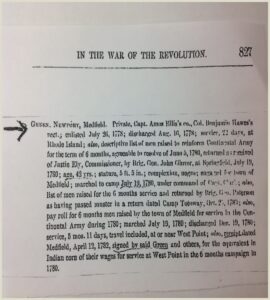

Newport Green was listed as a private in Captain Amos Ellis’s company. He enlisted July 26, 1778. He too was with the men raised to reinforce the Continental Army. He also served in the campaign at West Point.

Records show he received Indian corn in place of his wages during the West Point campaign. Green Street was later named after them. Newport Lane, off Green Street, is named for Newport Green.

Quock Walker, was an American slave from Barre, Massachusetts, who sued for and won his freedom in June 1781 in a case citing language in the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 that declared “all men to be born free and equal.”

The case is credited with helping abolish slavery in Massachusetts, although the 1780 constitution was never amended to explicitly prohibit the practice. Massachusetts was the first state of the union to effectively and fully abolish slavery.

By the 1790 federal census, no slaves were recorded here in Medfield or anywhere else in the state.