Oct 1, 2023

October is National Roller Skating Month, according to the Roller Skating Association International of Indianapolis, Indiana. – news item

Roller blades, skateboards and roller skates are popular forms of entertainment that are seen on the streets, sidewalks, skate parks, and rinks all over the world. All trace their roots to Medfield and to the invention of the first successful modern roller skate by James Plimpton.

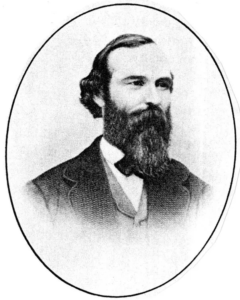

James Leonard Plimpton, the fifth of nine children born to Leonard and Sarah (Lane), was born on April 14, 1828. The Plimptons lived at 230 North Street, Medfield, next to what is now the hunt club land. As a boy in rural Medfield, James was brought up helping his father with the small family farm and with his father’s business of manufacturing cloth, which was run out of a small shop by their house.

James attended the nearby North School at the corner of North and Harding Streets. As a boy, James was a tinkerer who was fascinated with machinery. In that time of the Industrial Revolution, James was a natural mechanical genius. At age 16 he was apprenticed to a nearby machine shop, and before his 18th birthday he was foreman in a large machine shop in Claremont, New Hampshire. When James turned 21, he joined his brother and opened a business in Westfield, Massachusetts building machinery. Later, James opened a furniture business on his own in New York City. The young New England entrepreneur was making money and developing life-long business skills.

At age 32, during the winter of 1860–1861, James’ health began to deteriorate. On advice from his doctor, James took up ice skating, getting out in the fresh air of the ponds in Central Park. Plimpton noted an immediate improvement in his health.

Once spring set in and ice skating was no longer possible on the ponds, James wanted to find a way to continue his healthy exercise. In New York City, Plimpton invented the modern roller skate. His invention copied the ice skate, making it possible to duplicate the graceful type of skating he was able to do on the pond’s ice.

Plimpton’s “land” skates used two rollers under the ball of the foot and two under the heel. They were so arranged that both sets of wheels would rock in the direction in which the skater leaned, making possible the graceful curves of ice skating. His skate could be controlled by foot pressure. The wheels were made of boxwood. He called his invention “parlor skates.”

On January 6, 1863, he patented these “guidable parlor skates,” and for the next 17 years, federal patent law secured for Plimpton the exclusive right to manufacture, sell, and lease his invention.

Plimpton believed control of the market would be key to his success. Instead of conventional advertising, he sent out engraved personal invitations to the social elite of New York City, announcing a free demonstration.

His invention caught on with the who’s who of New York society, and soon an exclusive New York Roller Skating Association was formed, with Plimpton as its first president. Plimpton enlisted the aid of the New York association and in 1865 established the first public roller skating rink at Newport, RI. After two summers of exposing his invention to the wealthy of Newport, including Civil War hero and general William Tecumseh Sherman, Plimpton launched a well-planned broad marketing campaign.

Under Plimpton’s campaign, he would visit a city, rent a hall, and send out invitations. Once the skates attracted the attention of the town’s social and political leaders, others in the town wanted to see and try this new toy. Plimpton would then sell franchise rights for that city and move on to yet another city. Thus were opened more than 40 skating rinks, mostly in the south!

The owners of each franchise leased his skates at an annual fee. Convinced that he could make a greater profit, Plimpton always leased his invention, never selling his skates.

He also saw that his profit would best be made with the social elite rather than the lower classes and so favored local restrictions that ensured that roller skating would remain an entertainment for the upper class.

Plimpton claimed his roller skates would produce physical grace, good health, and moral uplift. Liquor, tobacco, flashy posters, and loud advertising were banned from all his rinks. Having three daughters, he saw roller skating as a “proper moral activity” for the young women of the Victorian era. This appeal to women was a significant factor in roller skating’s popularity.

By 1871, roller skating became a national craze, and much money was being made. Many others tried to copy his design and his roller skating rinks, causing Plimpton to spend much time in court. After long court battles, the U.S. Circuit finally ruled in favor of Plimpton saying that “Plimpton’s skates were truly new and not in the public use before his patent application back in 1863.”

All 14 defendants he had taken to court were ordered to pay damages.

At the age of 48 he was king of the roller skating empire. His Brooklyn, New York factory was now producing 2,000 pairs of roller skates a week but could barely keep up with the demand.

Plimpton then took his invention overseas, causing a roller skating craze to sweep through England in 1874. Again, due to its success, Plimpton now had to battle 169 copycats in the British courts. After much litigation, on Jan. 28, 1876, the British courts ruled in Plimpton’s favor, though his legal bills were enormous. From England, Plimpton took his roller skating craze to France, Australia, and the Dutch East Indies before returning to the United States in 1876.

In 1880 the expiration date of Plimpton’s 1863 patent caused a dramatic change to Plimpton’s fortune. New manufacturers and new rinks ended Plimpton’s dominance. But the Medfield inventor had made a considerable fortune in his lifetime and had unleashed a popular new form of entertainment and exercise, offshoots of which are still going strong today.

Here are links to:

(2) and an interesting article, translated from French.