Dec 1, 2023

There used to be a sign at the shack at the old Medfield town dump listing a few rules and regulations. At the bottom it said, “Per Order of Honey Bear Babcock, Dump Commissioner.”

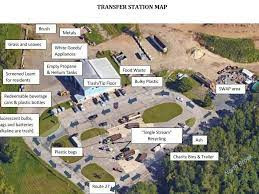

Fifty years ago, Medfield’s town dump was located off Grove Street. The site of that dump is the big grassy hill you see on your right as you drive on the “new” Route 27 past the DPW garage toward West Street. The old dump was filled to capacity, covered over, and replaced in 1986 by the new $800,000 transfer station shown in the aerial photo. (In addition to the primary function of receiving trash, the transfer station has become a minor summer social center, thanks to Nancy Irwin and the other swap area volunteers.)

This was in the days before Route 27 was relocated in the 1970s to a new road, called North Meadows Road, that began next to CVS and ran northward, crossing Dale and West Streets, past the transfer station and former state hospital, toward Sherborn. The old Route 27 snaked through the center of town from Spring Street to Main Street, left on North Street, up to Harding Street, left on Hospital Road, then past the hospital and down the hill out to present road to Sherborn.

It is worth noting that when the century-old state hospital was shut down, an open dump was left behind on the property. That trash pit (since cleaned up at a cost in the millions) contained eight junk cars, as well as medical waste, toxic chemicals, and general refuse, covering an area that measured about 1,000 feet by 50 feet.

The photo below (undated, but the car appears to be a General Motors station wagon from the late 1970s) shows the old dump, aka Mount Trashmore, very near the end of its useful life.

A Problem as Old as Civilization

In the old, old days of hunter-gatherers – say 10-12,000 years ago – trash and sewage disposal wasn’t cause for concern. There were far fewer people. They were always on the move, living off the land. They created far less trash, and it was generally organic and quickly broken down. But the agricultural revolution made it possible for people to live in larger groups, concentrating trash and sewage in their midst and creating a persistent disposal problem.

An easy “solution” was to throw waste in the river or sea; the public health consequences of this were not fully realized until the middle of the 19th century! Another option (more work) was to take trash out of the city and bury it, which became the practice in Asia about 3,000 B.C.E. and Athens about 500 B.C.E. About 100 B.C.E. Rome made a good start in creating a sewer system.

But for most of the two millennia that followed, city people in Europe and elsewhere wallowed in trash and filth and endured plagues. Over the last 200 years progress has accelerated…as has the amount of trash and sewage. Landmark developments in 19th century included Louis Pasteur’s discovery linking disease to microorganisms, and John Snow’s pioneering work in epidemiology, linking London’s cholera crisis to contaminated water taken from certain public wells – about the same time as London’s sewage crisis known as the Big Stink.

In that era, the primary method of transporting goods and people was via horse-drawn vehicles. In New York in 1900, the population of 100,000 horses produced 2.5 million pounds of horse manure per day, which all had to be swept up and disposed of…not to mention the need to dispose of tens of thousands of dead horses each year. Technology to the rescue! That problem went away with the introduction of the automobile – which as we know created its own problems.

On the trash front, New York City continued to dump a significant amount of its untreated trash miles offshore in the ocean until 1934. Many environmental laws have been enacted in the last century. However, despite those laws, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has come into being – it’s the size of Alaska!

In rural Medfield, until the 20th century, people generally burned and/or buried their own trash on their own land. The annual town report of 1917 is the first to mention a public dump; the fire department reported extinguishing a three-acre blaze at the dump. Dump fires were mentioned in many subsequent town reports.

Tim Flaherty’s Recollections

A century ago, before half the residents hired a trash pick-up service, most everyone living in Medfield knew where the town dump was located and what it looked like. There were few houses in that part of town. The dump stretched lengthwise for about one hundred yards.

People would drive up close to where they could throw their trash over the downhill ledge. The trash ran from food cans, jars, and bottles…to old mattresses, broken home appliances, old televisions, discarded living and dining room sets. Until the early 1970s, residents burned paper and other combustible trash in their backyard incinerators, and whatever wouldn’t burn was taken to the town dump.

Of course, if family members drove over to the dump in the 90-degree heat of the summer, they’d surely end up taking home a car full of house flies. On the way home, one had to keep their car windows down to get rid of the flies. Of course, windows would be open anyway, because few cars had A/C in those days.

On one occasion back in the mid-50s, two Medfield kids rode their bikes over to the dump to check it out. What they found at the front of one junk pile were small religious statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary along with other smaller, unfinished armless statues that looked like the Venus de Milo. They were rejects from a small art store managed by Ruth Ann Hardy that was located where the Needham Bank is today. When those kids decided to take the little statues home to surprise their moms and dads, one of the devoted mothers couldn’t help but remark that the boys happened upon a miracle due to the religious significance of the statues. For years afterwards, some of those statues were proudly displayed on the mantel piece of their homes. Indeed, one person’s trash turned out to be another family’s treasure.

On one memorable occasion in the Flaherty family, Mama Flaherty was combing the hair of her five-year-old son, Dennis. What Mama Flaherty didn’t notice was that Dennis grabbed a small metal Band-Aid box and threw it into the toilet while it was being flushed. However, the tin box stuck about halfway down the inside of the toilet, so it blocked the waste and water from properly completing the flush cycle. Consequently, the toilet sometimes overflowed if the plunger wasn’t handy.

After a frustrating week, Dad Flaherty had a new toilet installed. The next day Dad, my brother Todd, and I took the old toilet to the dump. When it was in the trash, we started throwing rocks at it for target practice and hit the very spot where the tin can lodged itself. There the troublesome toilet and tin can remained, home at last now in its final resting place.

Rats were a big problem. They were big and brown and would run around and eat the garbage that was mixed in with the trash in the dump. One way the town addressed the garbage problem was using “sanitation engineers,” two garbage men who drove through neighborhoods in Medfield collecting the garbage each family had put in their outdoor garbage pail. Everyone knew when the garbage truck made it into their neighborhood because of the pungent odor that followed the vehicle wherever it went. The two men would grin and bear the collection and at about 9am finally stopped at Ned’s Coffee Shop for breakfast before leaving Medfield and moving on to the next town.

In the mid-20th century, the dump was wide open, and there wasn’t a chain-link fence at the entrance to the dump. People would drive up quickly, open their trunks, and toss and go. But it was messy, and in the 70s the town put up a 10-foot-high metal fence that kept a lot of the paper trash from blowing away in the wind and spreading into the surrounding neighborhoods. Another improvement was having the trash covered and pushed forward by a bulldozer from the highway department. Most everyone agreed that covering the trash daily with gravel was the best possible solution to the rat problem, while following further sanitation procedures.

In the 1970s, Eugene “Babi” or “Honey Bear” Babcock was placed in charge as a groundskeeper of the Medfield dump, making the location cleaner and better organized. At one point, Babi found discarded televisions and took them home to his basement apartment on Main Street. Babi would fix them up and have them running like new. However, Babi’s tenure was short-lived because he neglected to unplug a TV while he was poking around inside it with a screwdriver. Babi was given a big-time shock that knocked him over backwards. That near fatal accident was enough to make Babi give up his newfound vocation.

Many people are familiar with the saying, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” In essence, Medfield has followed Rome’s ancient blueprint. Two thousand years ago people in Rome and other parts of Europe were throwing out trash and garbage in a similar manner to the way collection took place back in the Medfield of old. However, back then in time most people were responsible for disposing of their own garbage and waste by burying it in the ground. At other times the garbage was thrown into the streets where pigs would feed on it and render the area clean. The solid trash that was no longer functioning or of any value was often thrown into a nearby river. Historically, that whole process has been going on for the past 5,000 years. Getting rid of trash is a conundrum because in simplicity, people must rid themselves of trash and garbage and that calls for a great group effort of co-operation.

There’s no question, we are a wasteful species on planet Earth. The explosive population growth combined with an increasing desire for consumer goods, has led to an explosion in the amount of garbage we generate. The spectrum ranges from refuse produced by everyone in our daily lives, to highly toxic industrial wastes from the production of specialized goods such as cans, electronics, computers, cell phones and plastics.

Some of those items are recycled and re-introduced into the production cycle. Some of it is incinerated, and when this leads to the generation of electricity, it can be considered a form of recycling and conversion of waste to energy. The remaining waste ends up in a landfill. This basic method of placing garbage in large pits and covered at intervals, with layers of earth has remained relatively unchanged.

Despite all the improvements we have made to operating landfills, the real problem is simply their large numbers and the expanses of valuable real estate they occupy. All along, landfills have been a child of convenience. Time has come to develop and implement waste management systems that do not impair our environment, use up valuable resources, or place limitations on our future resources.

The universal answer to the outdated landfill is the transfer station, like the one Medfield built on North Meadows Road. People drive up to the transfer station and leave their trash that is systematically disposed of. Once left off in the building, a backhoe compresses it, and soon afterward it’s sent to the Wheelabrator Company in Millbury, Mass. where it is incinerated. That facility uses up to 1,500 tons of waste from homes and businesses each day as a fuel to create an energy ecosystem that generates reliable energy for the local utility.

The universal answer to the outdated landfill is the transfer station, like the one Medfield built on North Meadows Road. People drive up to the transfer station and leave their trash that is systematically disposed of. Once left off in the building, a backhoe compresses it, and soon afterward it’s sent to the Wheelabrator Company in Millbury, Mass. where it is incinerated. That facility uses up to 1,500 tons of waste from homes and businesses each day as a fuel to create an energy ecosystem that generates reliable energy for the local utility.

Via the transfer station, public involvement is essential. It has been said that waste is very democratic. Waste is produced by every one of us, and so we should all contribute to the solution. The objective must be to minimize the impact on the environment through a combined strategy of reduction, reuse, recycling and incineration or energy conversion. Instead of being the first choice, landfills should become the last resort.

We all depend on a healthy ocean, while a healthy ocean depends on us. That’s why we should be the change we would like to see in the world for the conservation of dolphins and other marine creatures while restoring the beautiful coral that line and live in our oceans.