Jan 1, 2023

Longtime Medfield resident Tom Connors sat as a judge in three Norfolk Country district courts and then moved up to spend over 16 years in the Dedham Superior Court. At the November 7 meeting of the historical society, he spoke about little-known aspects of the evolution of our court system. Much of Tom’s information came from Robert B. Hanson’s writings on Norfolk County history. Tom also spoke about some intriguing trials, which will be the subject of an article in next month’s Portal.

From the earliest colonial days, the Massachusetts courts have been a county-based system. Eastern Massachusetts was defined in its early days by the two main historical settlements – Plymouth Colony, founded by the Pilgrims in 1620, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony 10 years later, centered on the Shawmut Peninsula we know as downtown Boston.

The period after 1630 – the Great Migration – was one of explosive growth, considering the distance English settlers had to travel across perilous seas in ships of the era. The Plymouth Colony expanded through Duxbury and Scituate and inland and toward Buzzards Bay through what are now the present Plymouth and Bristol counties. The growth of John Winthrop’s Boston-based colony, from its inception a more well-heeled group, fanned out through the surrounding area – across the Charles to “Newtowne,” now Cambridge, and significantly for our purposes, to the southwest to a place along that river and near to the other major eastern Massachusetts river, the Neponset, Dedham.

Eventually, the “Dedham Grant” came to encompass all the land from what is today Boston’s southwest border to the Rhode Island line. That area eventually was carved into a myriad of towns; in the familiar story, the first settlement formally to separate was Medfield, recognized by the colony’s legislature as a separate entity in 1651.

The dividing line between the two colonies became known as the “Old Colony Line.” Oddly enough, in a state where many of our present municipal and county boundaries are irregular, formed after physical features or in some haphazard manner, this straight line, with some modification, remains as the border between present-day Norfolk and Plymouth and Bristol counties to the south.

The early settlers set ups a system of governance and adjudication of disputes. Research has suggested they were a fairly litigious people; we have records surviving of land disputes, stray cows and land damage, etc.

The entirety of the Massachuetts Bay settlement essentially south of the Charles was encompassed within a single sprawling county, Suffolk, taking its name from a region of East Anglia (which includes a small village called Metfield). This remained the case for over a century and a half from the early settlement of the Dedham Grant and other areas south of Shawmut Peninsula until just after the American Revolution.

This state of affairs led to an increasing dissatisfaction on the part of the people in this very large area of settlement remote from what was becoming the city proper. There were two principal areas of concern.

The first was simple geography and travel: the court was held in Boston, which was at the far northeastern edge of this large territory. If you lived in present-day Wrentham or Bellingham, you faced an arduous journey to address any legal matter you might have at the court in Boston.

The second reason was one which was economic and cultural. Boston was a growing port city, its economy centering on shipping and commerce, with its merchant class growing in prosperity and power. The Dedham Grant and other townships were largely agrarian, peopled overwhelmingly by families with small farms. It was bad enough to have to travel hours upon hours by wagon or horseback to have to seek justice; worse still to be believe you were looked upon as a country bumpkin once you got there.

As far back as 1726, the representatives of the country towns petitioned the General Court, the colony’s law-making body and predecessor to our present-day legislature, to be made a separate county. This effort was repeated with regularity over the next 60-plus years, perhaps a dozen times, without success. The 1726 petition set forth a litany of reasons:

- The near impossibility of performing jury service, which required relocation to Boston from their farms for the duration of the court sitting

- The bad mesh of the two areas economic bases, noting that over 90 percent of the civil cases heard at court involved trade and business, in which the farm folk were not well-versed. (Petitioners believed that were separation allowed, the area’s cases could probably be disposed of in just four days a year.)

- Most of the judges lived in Boston and were ignorant of country affairs

- Matters such as probate of wills to pass property needing to be effected so far away posed great inconvenience

- Money always being important, that on the criminal side, the country towns were being hit with a disproportionate share of jail costs [sounds as though they viewed criminals as largely the big city’s problem, not theirs.].

In this we see a growing sense of estrangement in that era between based on different economies and development and what has been described as a “growing prejudice against the Boston clique” that was seen as controlling much.

[In later history we’ll see such sentiment play out in Shay’s Rebellion where Massachusetts farmers revolted during the very early years of the American republic against what they saw as unfair treatment by the mercantile elite.]

Indeed, the main impediment to the effort was the need to have both legislative bodies approval. The 1726 application was approved by the House of Representatives, but rejected by what was then the upper house, the colonial Governor’s Council. That body and its post-Revolution replacement, the Senate, were perceived as controlled by Boston interests and continued to stymie the efforts, although the country towns persisted in pressing their representatives to seek a divorce from Suffolk County.

As time went on, events had caused people to think more about counties as significant entities. In a Massachusetts where the town and town meeting acting under the colony’s overall government had always been the center of things, events leading up to the Revolution had served to disrupt matters. With the revolutionary ferment intensifying through the British taxation efforts and the sending of British troops to occupy the city, one of the by-products was a clamping down of the authority of the state-wide General Court to act. Into what was essentially a power vacuum, the need grew for geographic areas to act for the common good in a more regionalized basis than just the small individual communities.

A strong example we see in the Suffolk Resolves, a very important and influential document setting forth in strong terms opposition to British oppression and resolve to address it through refusal to pay taxes, boycott of British goods, and encouraging formation of colonial militias. It was drafted in Milton (the house is still there on Canton Avenue) after the men had met initially at Ames Tavern in Dedham. It’s noteworthy that 74 of the 79 of its delegates came from the country towns…and only five from Boston.

Once the Revolution was over, the move toward a separate county picked up steam. It’s interesting that added to that litany of reasons for the necessity of not being linked so tightly to Boston, a new one was now articulated, described by a chronicler of Dedham history at the time, Erastus Worthington, as “the universal antipathy which prevailed in the country towns against the members of the legal fraternity.”

Indeed, Dedham town meeting issued an instruction to its representative: “We are not inattentive to the almost universally prevailing complaints against the practice of the order of lawyers . . .we think their practices pernicious and their mode unconstitutional” demanding that state government place “restraints” on lawyers so “that we may have recourse to the laws and find our securities and not our ruin in them.” It then directed that if such efforts appeared impractical that it would be preferable that the role of lawyers “be totally abolished.” (!)

That direction immediately prefaced another – that the effort to establish a separate county be renewed. In addition to the customary reasons, was added another – “should courts of justice be erected in some country town within the county, we expect (at least for a while) that the wheels of law and justice would move on without the clogs and embarrassments of a numerous train of lawyers. The scenes of gaiety and amusements which are prevalent in Boston we expect would so allure them, as that we should be rid of their perplexing officiousness.”

[For those of you interested in the politics of the time, this sentiment had a political dimension. This was the era when a two-party system was beginning to emerge, between the Federalists and the Democrat-Republicans – think of Alexander Hamilton (whom we all know from Broadway), proponent of the mercantile interests, and Thomas Jefferson who espoused a kind of agrarian utopian vision of a republic of small farmers. This was wholly in-line with the prevailing beliefs of the pious farmers of Norfolk County – estimated Dem-Republicans outnumbered Federalists 3-1 in Dedham, while as a group, members of the bar were overwhelmingly Federalist.]

Establishment of the County

Finally, in March of 1793, the country towns prevailed, and the General Court of the now Commonwealth of Massachusetts approved the partition of Suffolk, creating a new county. The bill was then signed by the governor, John Hancock. There is no record of how it came to be called “Norfolk.” Historical records say the county’s representatives met at Gay’s Tavern in Dedham, and they tossed around the names “Union” and “Hancock,” maybe to curry favor with the incumbent Governor, but they couldn’t reach a consensus. When the bill to create the county was initially sent to the legislature for submission, the county name initially was blank. An unknown person wrote in “Norfolk.” The choice of that name created something of an anomaly – the name connotes “north” and in England, Norfolk County sits appropriately north of Suffolk County, that name connoting “south.” Massachusetts’ new division placed Norfolk below Suffolk.

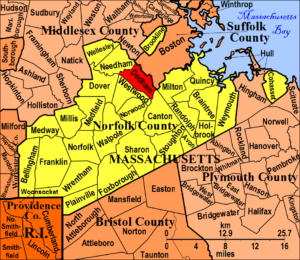

Today the County is composed of 27 towns and one city, Quincy, however, it looked different at its formation. Because the city of Boston consisted only of what’s now the downtown area, the bulk of Boston’s present neighborhoods which lie to its south were separate towns – Dorchester and Roxbury which included present West Roxbury and Hyde Park. These were initially part of the county, and they remained so until they were later annexed to the city, but not until many decades later. Hyde Park was not annexed until 1912, and up to that time had remained part of Norfolk County.

Today the County is composed of 27 towns and one city, Quincy, however, it looked different at its formation. Because the city of Boston consisted only of what’s now the downtown area, the bulk of Boston’s present neighborhoods which lie to its south were separate towns – Dorchester and Roxbury which included present West Roxbury and Hyde Park. These were initially part of the county, and they remained so until they were later annexed to the city, but not until many decades later. Hyde Park was not annexed until 1912, and up to that time had remained part of Norfolk County.

The separation actually was not met with unanimity; several towns at least initially did not like the change. Both Brookline and Weymouth protested, in both cases for reasons that included their lack of proximity to the portions of the county expected to become the shiretown of the new county [county seat, in the rest of America]. Neither protest was successful, and both remain part of Norfolk.

On the other hand, two other towns, Hingham and Hull, were successful in resisting inclusion in the new county. Both towns had significant maritime interests, and one suspects that now being part of an entity dominated by inland farming communities was not at all appealing. The Legislature listened, and shortly after the setting up of Norfolk, but before the bill’s effective date, it passed an enactment exempting both towns, thus leaving them part of Suffolk. This had the odd effect of leaving both of those towns better than 15 miles from the remainder of Suffolk County, and it proved untenable; ten years later, the two towns went back to the Legislature and got approval to become part of the bordering land to the south, Plymouth County, where they remain today.

These various movements over the years led to the anomaly that the County ended up having two of what geographers refer to as “exclaves” – towns which were isolated and not contiguous to the rest of the county. The first of these, Brookline, became geographically separated from the rest of Norfolk County when areas like West Roxbury became part of Boston due to annexation. The second is Cohasset which arose from a rather curious circumstance that it did not join its two neighbors Hull and Hingham in opting out.

If you look at a map of the county and its southeastern boundary, you’ll notice that Cohasset is separated from the remainder of the county by the towns of Hingham and Hull; however, you’ll notice that the southern boundaries of all three towns are the straight-line that demarcated the old Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies. So if anyone’s in the wrong place, it’s those two towns, not Cohasset!

Selecting a Shiretown

This occasioned some controversy. Earlier unsuccessful bills had mentioned the towns of Braintree (which then included Quincy), Dedham, and Medfield. At the beginning of the county’s existence and in its early years there had been efforts made to make Braintree, Milton, or Roxbury the shiretown. Medfield’s central location made it a candidate; however, it took itself out of the running in no uncertain terms! According to one record, the town declined nomination, stating: “the practice of visiting the court room during the trial of cases would be prejudicial to habits of industry in the citizens.”

One person put it even more bluntly: “our young men will fall into habits of idleness and spend too much time in gratifying curiosity by attending trials in court.”

Again, the distrust of the legal profession and a strong fear that youth would be corrupted, enticed away from farm work to observe the antics of the members of the bar. Ultimately the distinction of shiretown went to Dedham, which after all was the “parent” town of much of the county.

The Courthouse

So, in 1793 there was a new county with a new shiretown, and a courthouse needed to be constructed. The county at its founding contained about 25,000 inhabitants. At first, court convened in a church meetinghouse in Dedham. That unheated facility proved inadequate – one of the very early court sittings declared it unfit “by reason of coldness” and was adjourned to the Ames/Woodward tavern, which stood roughly where the registry of deeds/jury assembly building sits across from the present courthouse. (That was a common practice at the time, as taverns served multiple purposes.)

Canvassing for a court site then went on, and space was found in front of the First Parish Church in Dedham on the church green across Court Street from the present site. It went slowly – the construction stretched over several years, one prominent lawyer likening the pace of work to “a snail’s gallop” (some things with public constriction never change).

When the wooden building was finally completed, it did not meet with everyone’s liking. It had low ceilings and was unable to accommodate enough people; the Supreme Judicial Court on its first sitting there in August 1796 found it so stifling that they instead returned to the meetinghouse.

One by-product of this difficulty was that it caused the legal community to come together in a very noteworthy action – establishing BANC, the Bar Association of Norfolk County. In 1795, the prominent lawyer Fisher Ames summoned the county’s lawyers to a meeting for that purpose. [Ames defeated Sam Adams and was elected to the very first Congress. Ames was a staunch Federalist and supporter of Washington’s policies, and he was a great orator: there is a plaque on the site of his law office in Dedham].

Among those founding members of the association was a lawyer named Horatio Townsend, a native of Medfield. Townsend is a person of note in Medfield: in 1797, he bought the Dwight-Derby House and its surrounding 16 acres. (His daughter Mary married John Barton Derby, scion of a wealthy Salem merchant family, giving the residence half of its name). Townsend later served as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas, a forerunner of the Superior Court.

The BANC continues in existence today; it’s one of the oldest bar associations in the United States.

The Present Courthouse

So, the County now had an association of its lawyers, but it was still dealing with a small, drafty, and inadequate courthouse. Beyond its small size and other shortcomings, it was a wooden structure was thus seen as a major fire risk as the repository of the county’s public records. The county finally was prevailed upon to plan construction of a new fireproof courthouse made of stone in Dedham Square near the wooden building. The bar had high aspirations for the structure to be built; the association’s then President James Richardson, also of Medfield, waxed eloquent that as a symbol of the county’s dignity and prosperity, something more was needed than a simple utilitarian structure as the county initially envisioned, but rather: “a magnificent temple of justice [which] would inspire an elevation of mind and contribute to cherish[ing] those feelings of reverence for the administration of the laws which is so desirable to cultivate in a free community…”

To that end, the county commissioned a noted architect of his day, Solomon Willard, to see to its design. Willard is best known as the architect and superintendent of the erection of the Bunker Hill Monument. His commission from the county was to design a building modeled on “an ancient Grecian temple, with columns at both ends” along pure and simple lines.

To that end, the county commissioned a noted architect of his day, Solomon Willard, to see to its design. Willard is best known as the architect and superintendent of the erection of the Bunker Hill Monument. His commission from the county was to design a building modeled on “an ancient Grecian temple, with columns at both ends” along pure and simple lines.

This choice was not happenstance; it reflected a very strong and noteworthy trend in courthouse construction of the era. In the early 19th century, as America approached its 50th anniversary, there was an increasingly prideful linking of its democratic form of government to the origin of Greek democracy in antiquity. This sentiment was enhanced by the Greek War of Independence, which was going on at that precise time, as the “Cradle of Democracy” warred against the autocratic Ottoman Empire. Americans identifying with the new Norfolk courthouse was to follow classic lines of Greek revival style with strong columns and a triangular of pedimented roof.

Willard’s set to work and first needed a supply of granite for the building. His monument in Charlestown needed a very large amount of granite, and he had found that quantity available in Quincy’s quarry, many miles away (this prompted the building of one of the country’s earliest railroads to move the rock to a wharf in Milton from where it would travel down the Neponset and across the harbor to Charlestown). For the Dedham courthouse, the materials were much closer at hand, in our town, the granite was quarried from what is now Rocky Woods Reservation.

On July 4, 1825, with fanfare, the cornerstone was laid. This was a big deal – a history of the time records that it was occasioned by the firing of cannon and a procession to the meetinghouse with prayers offered and an address from the Masonic chaplain. This was followed, it is recorded, by a dinner with multiple toasts and music.

Construction was completed and the Courthouse ready to be open two years later. On February 20, 1827, an opening ceremony and dinner was held by the Norfolk Bar, with all the justices of the SJC, the attorney general, and Solomon Willard in attendance. The SJC CJ, Isaac Parker, gave remarks about what a grand and beautiful building it was.

This was all true. It stood two stories tall, with porticoes at either end, each supported by four Doric columns nearly 21 feet high. It featured a bell cast by Paul Revere in 1790 which had been used in the original courthouse to summon for the start of the court session.

Impressive, yes, but the building still had its issues, not dissimilar to its predecessor. It lacked plumbing; running water; and any effective system for heating the interior of the two-story structure. Its design had left it open to cold drafts of wind through its large central hallway. Indeed, one of the clerks who worked in the building described it as: “barren and destitute of every convenience demanded alike for health, comfort, and decency.”

During the years after the first courthouse’s opening, change was afoot in this county of farmers. As the years went by, the towns were growing in population, and the stirrings of the early Industrial Revolution were bringing additional legal business. For the town of Dedham and its businesses, the establishment of a county court and its increasing business proved to be a boon.

For one thing, there was no scheduled docket of cases, but rather, when in the early years of my practice it still to some extent existed, was referred to as the “cattle call.” Everyone with a case during that sitting – lawyers, parties, witnesses – was expected to be present in case their case might be called. This necessitated overnight stays at the inns and taverns for lawyers and witnesses coming from any distance and remaining beyond the first day.

One historian noted that the opening of the sitting prompted something of a carnival atmosphere, descriptions that oyster vendors appearing in the square and the local tradesman taking advantage of the sudden influx of business from a well-heeled clientele.

However, as roads improved and trains came, this boom subsided; indeed, this resulted in a steady dwindling of the number of taverns and boarding houses. The population, however, was still on the rise – up to roughly 110,000 by 1860 – and as the county prospered, the caseload was increasing.

Some of the obvious defects that had plagued the building finally were rectified, with the addition of gaslights and running water in 1854, and a fireproofing to assure security of records a few years after. However, the capacity of the 1827 building was insufficient for the county’s growing legal business.

While there was talk of building a second court building across the street and transferring some functions there, a decision was finally made to enlarge the existing structure by adding wings each side. Some protested the plan, even raising a petition opposing that alteration, arguing it would mar the building’s beauty, and this did not abate when the contract was awarded and the work finished.

Once again, a prominent Boston architect was engaged, Gridley J.F. Bryant, who is known for some significant structures throughout New England, including Boston’s old city hall and the Charles Street jail (now the Liberty Hotel). The alteration did add significant square footage.

However, one aspect served to stoke the preexisting controversy – in addition to the new wings, the courthouse was now adorned with a massive multi-story dome. We are all familiar with the dome which remains to the present day. The purists did have at least a conceptual point, as domes are characteristic strictly of Roman building style, and the new work left the classic Grecian temple topped by an architectural incongruity.

So why did this happen? Well, courthouse rumor of the day was that Gridley had been retained to design a domed building in Providence and had been left with an extra set of plans he had worked on, which, conveniently, he now pressed on the Norfolk County fathers as a simply great idea for the Dedham structure. [Cynics might say that some aspects of public construction haven’t changed so much in 150 years!]

The work was completed in 1862, expanding the number and variety of court sittings, probate in addition to the newly founded Superior Court. Indeed, its size permitted a wide variety of uses – it is recorded that in the year of its opening, dozens of county residents were examined by a physician to determine if they should be exempt from the Civil War draft.

Within just 30 years, the building again had become inadequate. Attempts were made to tweak through alterations, but it became apparent that more space was needed. In 1892, contracts were awarded for a very substantial enlargement with additional wings and a revamping of the interior space. This renovation was quite carefully carried out.

Polished oak was used in the interior work and marble used on interior lower walls and floors, some imported from Italy. Rocky Woods again provide the cut granite blocks for the wings, and the dome was replaced with a larger and grander one covered in copper.

This was the last large-scale work, and the courthouse today remains from its exterior largely unchanged. Its significance is attested by its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, and it is also designated a National Landmark. Whereas there are some 90,000 entries on the NRHP, there are only 2,500 National Landmarks, among them Independence Hall and the Alamo.

End of part 1 – next month will feature some intriguing trials that have taken place at the courthouse.