Mar 1, 2023

Longtime Medfield resident Tom Connors sat as a judge in three Norfolk Country district courts and then moved up to spend over 16 years in the Dedham Superior Court. Dedham courthouse has been the site of many famous trials -and it will be the site of the trial of Brian Walshe, who is accused of murdering his wife Ana and dismembering her body last month.

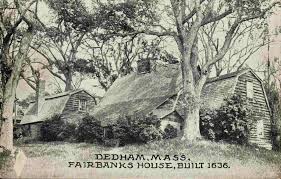

Jason Fairbanks came from of a prominent family. The Fairbanks house in Dedham is the oldest surviving wood-frame structure in North America. Built in 1641, it belonged to the same family for over 250 years; descendants included Charles Fairbanks, Theodore Roosevelt’s vice president.

Jason struck up a relationship with a young woman who lived nearby, Elizabeth “Betsey” Fales, who was 18. Her family didn’t approve: Jason suffered from health problems, including a withered arm resulting from smallpox, and he was not viewed as a suitable prospect. Because of that, the two would meet in secret in a grove of trees a short distance from her residence. Reputedly, the two had an on-off relationship with Elizabeth breaking up, then taking him back.

On a late spring day in May 1801, Jason staggered into her home, with stab wounds and covered in blood. He told her family that Betsey had committed suicide and that he had then attempted the same but was unsuccessful. Her parents ran to the woods and found her dying, later determined that she had been stabbed 11 times. Jason’s injuries were fairly severe, and he was left at the Fales House and treated.

The circumstances of Betsey’s death, however, promptly gave rise to very serious doubts about his version of events. Chiefly, the 11 stab wounds to Betsey included one to her back, making it implausible that these were self-inflicted. An arrest warrant issued, and Jason was bound over to the next sitting of the grand jury, which returned indictment for murder in August. Still suffering from his own wounds, he had to be carried on a litter from the Fales’ home to the county jail, where he was held in custody.

The case and the trial were a sensation, both locally and in the wider world. Betsey’s funeral reputedly was attended by 2,000 people. When the case was called for trial, the crowd was so large that it had to be moved from the original wooden courthouse and into the meetinghouse. The trial began on August 6—the day after the return of the formal indictment and amazingly by our standards, less than three months after Betsey’s death.

Prominent lawyers squared off in the case—AG John Sullivan prosecuted and Harrison Grey Otis defended. The prosecution made out a strong circumstantial case. (Eyewitnesses aren’t always the best evidence.) Its witnesses testified that Jason had expressed frustration with her ambivalence about their relationship, that he had told someone that he planned to meet with her and “settle the matter,” and that he had made threatens to harm her parents. In addition, a farm hand employed by the Fairbanks family recounted that Jason had borrowed the jackknife which had caused her death.

Sullivan also pointed out that Betsey’s 11 wounds including the one to her back. The defense case was difficult—it harped on Jason’s physical infirmities, especially his disabled right arm, as a basis for innocence. Its theory was a lovers’ suicide pact (something Jason himself at one point denied).

The nature and number of Betsy’s wounds likely carried the day—after 10 hours: conviction. Jason was returned to the Dedham lock-up to await execution. In those days, appeals were extremely limited—the SJC itself heard the murder case, and punishment—prison or execution followed trial in a matter of a month or even of days!

But the story was not over. In this small town, some people believed he was innocent, chief among them his family. The county jail was a simple structure put up after the county’s establishment, located on Highland Street, a few blocks from the courthouse. It was later replaced by a stone structure on Village Street (now condos) which remarkably served as county jail from 1817 to 1989.

On August 17, just nine days after his conviction, a group of Fairbanks’ relatives and a few friends managed to break Jason out. They headed north, planning to make it to Canada.

The escape caused a public uproar, and the authorities acted swiftly. A bounty of $1,000 was set for his capture. A party of three men pursued Jason’s group into New York state, two men from western Massachusetts and Seth Wheelock, a great-great grandson of Ralph. They found Jason in Whitehall, NY where he had stopped to eat breakfast as he was about to board a boat that transited a canal onto Lake Champlain, destined for Quebec. Stunned by the appearance of this posse, he was taken into custody for his return.

Once in Massachusetts, the state government stepped in and secured an order that he not be returned to Dedham but be remanded to the secure Suffolk County jail. There he stayed until September 10, when the Norfolk sheriff arrived to collect him.

With a large contingent, including two calvary companies and volunteer militia, he was escorted from Boston and arrived at the Dedham jail. At 3 p.m., he was taken the few blocks to the common (Route 109). There, amazingly, were assembled 10,000 people, five times Dedham’s population. It was reported that 711 carriages arrived in town with spectators.

Even after the execution, the case retained notoriety. From the first, newspaper accounts of the crime had stressed its lurid aspects—two young people, an illicit love, and a bloody ending. There now followed a flurry of pamphlets and papers about the case which seemed to capture the public’s imagination. The growth of literacy and of publishing had been spurred by a rise of works of “sentimental fiction;” in addition, in addition trial reports, which had been the province of lawyers and legal scholars, now began to find wider publication and readership—at least for cases where that paralleled those presented in the day’s lurid fiction.

One of the first entries in this blizzard of published stories, The Solemn Declaration of the Unfortunate Jason Fairbanks, purported to be his jailhouse account of Elizabeth’s death, designed to cast his case sympathetically. Other publications took various tacks, pro and con conviction, all airing the case’s salacious details. The extent of the public’s fixation on the case may best be represented by the fact that a traveling waxworks museum even included a depiction of Jason among the wax likenesses of Washington, Napoleon, and Shakespeare’s Othello!

Today, if you visit the Old Village Cemetery behind St. Paul’s Church, you can see both graves only about 30 feet apart. Jason’s lists his dates with no detail.

Elizabeth Fales’ bears a haunting inscription which reads in part:

“Since God Decreed You should be Slain,

We’ll Cease to Mourn, Nor Dare Complain.”