Patriots’ Day (Patriot’s Day in Maine) is a holiday commemorating the opening battles of the Revolutionary War, the battles of Lexington, Concord and Menotomy (now Arlington). In Massachusetts, the day is marked by battle reenactments, ceremonial events, and the beloved Boston Marathon.

In 2025, Patriot’s Day occurs on April 21st for Massachusetts and Maine, which were originally part of the same state, while the states of Florida, Wisconsin, Connecticut and North Dakota still observe the original date of April 19. In Massachusetts and Maine, since 1969, the holiday has been observed on the third Monday in April, creating a three-day weekend, which for most people is the extent of their interest in Patriots’ Day. And I felt the same. Tasked with writing about Medfield’s Revolutionary days, I had little inspiration until an extraordinary letter practically fell from our archives into my lap, and again I had that wonderful feeling of discovery that comes from touching a piece of history.

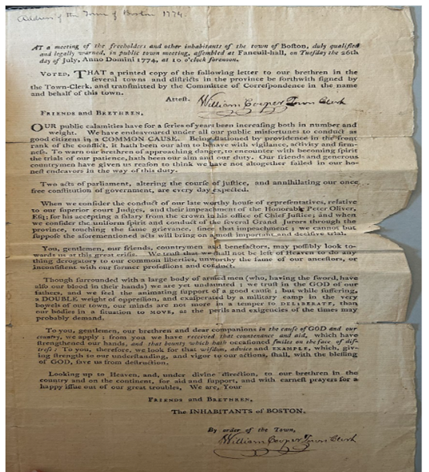

This is a letter from the “Inhabitants of Boston,” signed by Town Clerk William Cooper, addressed to the Town of Medfield through Town Clerk Enoch Adams, pleading for help against the British Navy, now embedded in Boston, “in the very bowels of our town.” The Port Act had blocked all trade as punishment for the recent Boston Tea Party. Not only were the colonists deprived of food and goods through their own port, but they were also expected to repay the East India Tea Company for the tea they had dumped into the harbor.

To clarify this letter’s place in time, the Tea Party had occurred on December 16, 1773, the letter was written on July 26, 1774, and the First Continental Congress would be held on October 14, 1774. This document was written on the very brink of the Revolution. Similar letters had been sent to the other “country towns” in Massachusetts. There should be, if there isn’t already, an entire book, or even a historical novel, about Medfield’s response to Boston in its time of need.

I noticed that the letter was “transmitted” from the Boston Committee of Correspondence, a name I vaguely recalled from my high school history classes, along with the fact that the first Committee of Correspondence was formed by Samuel Adams in 1772. This Committee functioned as an emergency network of communication among the thirteen states, to share information, organize political activities, educate citizens about their rights, and attempt diplomacy with the Crown as necessary. It was the public face of the movement to unite the colonies in opposition, while the Sons of Liberty was another group that worked behind the scenes on direct political actions like the Tea Party itself. Most members of the Boston Committee were also members of the Sons of Liberty. All were true Patriots.

What follows is a transcription of the letter from Boston to Medfield, with original spelling and punctuation retained as much as possible:

For context, and Medfield’s own response to the letter, I turned to William Tilden’s History of the Town of Medfield Massachusetts 1650-1886, which tells us that this was not the first letter sent to Medfield by the Boston Committee of Correspondence. Let’s go back to late 1773, when Boston sent a statement of the “rights of the colonies, and of this province in particular, also a list of infringements of those rights,” (Tilden 160) and Medfield “voted as the clear Sence of this Town that the rights stated are in substance the just rights of the Collonies and of this province; and that the Infringements there Innumerated are Real and Heavy Grievances which we have long and Justly complained of, and if continued will totally destroy the Libertys of the Province and the Continent of America” (Tilden 159).

Medfield had already pledged its support for the revolutionary cause, so the writers of the July 26 letter knew they had a sympathetic audience in Medfield. Another letter from the Committee had been received by Medfield near the end of 1773, “to which the town voted the following reply” on December 14:

We esteem the free and full privileges of Englishmen as the birthright of every American, nor do we know any reason why the distance of three thousand miles from the island of Great Britain should curtail or abridge them, especially when by charter grant they are solemnly ensured to us as though we were born within the realm of England. . .(and) we hold it a fundamental principle not tamely to be yielded up to any man or body of men on earth, that the rights of taxation in the British colonies in America is visited solely in the Houses of Assembly of the respective provinces, who are made up of men vested with authority by the free vote and suffrage of the persons on whom the tax is to be laid. It is with grief we behold this fundamental principle, this charter grant, become a matter of dispute and contention (Tilden 160).

The same letter from Medfield, poignantly, contains several mentions of the evil of slavery, and ends with:

We wish to maintain constitutional liberty ourselves, and cannot endure the thoughts of its being withheld. . .for no other reason that we can conceive of but because God of nature has been pleased to tinge their skins with a different color from our own. . . .Our earnest wish is that the things which belong to the nation’s peace may in no one instance be hid from our eyes. We remain united with our brethren in one common cause (Tilden 162).

Tilden tells us that (t)he committee to prepare this reply was chosen December 14. Two days afterward, the destruction of tea in Boston Harbor occurred (Tilden 162).

Now, back to the summer of 1774 in Medfield, as the town leaders decide how to respond to the emergency in Boston. “Moses Bullen was chosen Representative to the General Court at Salem, with the following instructions: “(Tilden 162) . . .You are hereby directed not to submit or yield obedience to any acts of British Parliament, or ministerial instructions that infringe upon and dispossess us of our natural and charter rights, civil or religious” (Tilden 162-63). Medfield then chose its own Committee of Correspondence, namely Simon Plimpton, Eliakim Morse, Seth Clark, Daniel Perry, and Moses Bullen. By vote that fall, the town agreed to spend 17 pounds “to double its stock of ammunition.” At the December 26, 1774 Town Meeting, exactly five months since the letter from Boston seeking Medfield’s help, the town voted to “inlist” and hold “at the shortest notice…¼ part of militia to march in Defence of the Province. The soldiers’ wages were settled, and it was “voted that the number of minute-men should not exceed twenty-five” (Tilden 164).

In terms of aid for Boston during the shutdown of its port, the town of Medfield along with “many towns in this and other states” sent money and supplies. Medfield’s contribution was “132 lbs of pork, 402 lbs of cheese, and 22 cartloads of firewood” (Tilden 164). A historical novel begs to be written. This three-day weekend might be a good time to start. Anyone?