Medfield’s Town History

Founded in 1649, and incorporated in 1651, Medfield is a town steeped in history. It survived the destruction of half its homes in the King Philip War, supported the anti-slavery movement through underground railroads and became home to the second largest straw and felt hat factory in the United States and several other small industries including a manufacturer of cut nails, a fork factory, a company for the manufacture of boots, a wire factory, a box factory and a substantial company manufacturing horse-drawn carriages.

Beginning in the mid-1800s and continuing well into the 1900s, Medfield established itself as an appealing venue for celebrated artists and musicians, and in 1896 it became home to the Medfield State Hospital. The 20th century brought both growth and conservation and preservation movements. Today Medfield is a 21st century Boston suburb renowned for its school system and its still-rural character.

The town is also home to a large collection of First Period American homes. A minimum of three Medfield homes date, at least in part, to the middle to late 1600s: the Peak House, the Dwight-Derby House, and the Lowell Mason House.

The Early Years

The story of Medfield begins in Dedham, whose expansive territory originally included what are now the towns of Medfield, Norwood, Walpole, Norfolk, Wrentham, Franklin, Bellingham, Dover and Needham, plus parts of Natick and Hyde Park. Dedham was incorporated in 1636, and by 1640 Dedham men started harvesting the grass that grew in the meadows along the Charles River. These grasses became important for feeding the cattle and livestock back on the Dedham farms. Our area was first known as Dedham Village.

Over the next decade, a number of Dedham families determined to move here permanently. In November of 1649 Dedham held a town meeting that approved laying out an area for a new town. This was accomplished in the early spring of 1650, and very nearly corresponds with the boundaries of the present town. Also included in the layout of the new town of Medfield was a grant by the General Court of land west of the Charles River, now Medway and Millis. The thirteen original settlers paid fifty pounds to the inhabitants of Dedham in compensation for the land.

Ralph Wheelock, a graduate of England’s University of Cambridge and considered the founder of Medfield, proceeded with Thomas Wight and Robert Hinsdale to the new settlement, which was finally incorporated as the 43rd town in Massachusetts on June 2, 1651. Twenty additional men were accepted as townsmen and grants of land made to them that same year. By 1660 the town was laid out and new families admitted, thus increasing the population to 234.

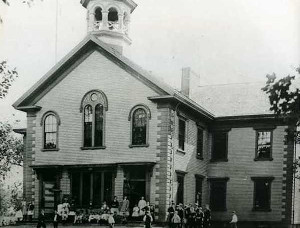

Education was very important from the start of the settlement. In 1655 the settlers voted fifteen pounds “to establish a schoule for the education of the children and was held in the homes of townspeople.” Ralph Wheelock became the first schoolmaster. The first schoolhouse was built in 1666 on the south corner of Janes Avenue and North Street. A later school on Pleasant Street was named after Ralph Wheelock, as is the present elementary school on Elm Street.

King Philip’s War, 1675–1676

The core issues leading to this war were land disputes resulting in loss of native lands due to what the natives saw as the colonists’ land theft, the population explosion among European settlers resulting in loss of native lands—and, of course, politics, especially between the native tribes.

The core issues leading to this war were land disputes resulting in loss of native lands due to what the natives saw as the colonists’ land theft, the population explosion among European settlers resulting in loss of native lands—and, of course, politics, especially between the native tribes.

In December 1620, 102 pilgrims from Plymouth, England, landed on Cape Cod. They quickly formed an alliance with Ousamequin, sachem of the Wompanoag confederacy, which had been depleted by smallpox and needed help against their Narragansett rivals.

Ousamequin, who had the title Massasoit, meaning Great Sachem, was aided by Squanto, who had earlier been kidnapped by the English, enslaved and taken to Spain. He later made his way to England and then back to Plymouth, where he was the only remaining member of his tribe.

Massasoit formed close personal and political ties with Myles Standish, William Bradford, Edward Winslow and other colonial leaders. (Winslow earned Massasoit’s eternal gratitude in 1623 when he nursed the gravely ill sachem back to health.) This alliance was critical to the survival of the English in the early days, and it lasted until Massasoit died about 1661.

After Massasoit’s death, the alliance began to fray. Massasoit’s sons, Wamsutta and Metacomet, asked the court in Plymouth for English names and thus became known as Alexander and Philip. Alexander was summoned to appear before the leaders at Plymouth, and after staying in Plymouth Governor Winslow’s house, he became deathly ill and died. Philip then became the Wampanoag sachem. He believed his brother had been poisoned by those at Plymouth.

The English population of 102 in 1620 grew in 50 years to around 40,000 in New England, thanks to the high birth rate and the Great Migration of immigrants from England of the 1630s. Meanwhile, the native population dwindled to a roughly estimated 20,000, due in significant part to diseases brought by Europeans.

The English brought not only their religion but also English common law, administered by the colonists’ courts. English common law included the concept of land ownership and owners’ rights. This was utterly alien to the natives, who had always come and gone and hunted wherever they pleased—and who did not take kindly to having courts fine or otherwise punish them and take their land for trespassing on areas they had always used. The land issue intensified as the English population exploded, forcing natives to lose more and more of their lands, pushing them further and further west.

Things came to a boil in King Philip’s War of 1675–1676. Natives saw no recourse to saving their homeland but to attack and set fire to scores of towns across New England.

During King Philip’s War, Medfield became the frontier town when Mendon was abandoned in 1675. On February 21, 1676, somewhere between 300–1,000 Native Americans—under the command of Monoco—burned 32 houses, two mills and many barns.

Seventeen colonists were killed, including Timothy Dwight, the original owner of the Dwight-Derby House on Frairy Street. An unknown number of Native Americans were also killed. Two streets serve as a reminder of those fateful days—Philip and Metacomet (Philip’s native name). After King Philip was killed in August of 1676, the settlers rebuilt and repaired the damage to their farms and mills, with monetary assistance and relief from taxes from the provincial legislature.

The Revolutionary War

Patriotic fervor was evident in 1774 when the town sponsored Minutemen to fight in the battles of Lexington and Concord, although they did not arrive in time to fight. One hundred and fifty-four Medfield men, however, fought during the Revolutionary War and three gave their lives for American independence. That made the ratio of soldiers one for every five of population. By 1787 a new oath was required of the town officers who renounced loyalty to the king and swore allegiance to the new sovereign, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Industry Takes Root

In 1800 the population of the town reached 745 and small industries began to take root. Straw manufacturing commenced in town for the first time in 1801 when Johnson Mason and George Ellis began manufacturing straw bonnets in what later became known as the Lowell Mason house. The manufacture of hats became the principal industry of the town until well into the 1950s. At its height, the E.V. Mitchell Hat Factory was the second largest straw and felt hat factory in the country, employing over 1,000 workers—more than the population of the town itself. Workers came from as far away as Maine and Canada to work at the North Street plant.

In 1800 the population of the town reached 745 and small industries began to take root. Straw manufacturing commenced in town for the first time in 1801 when Johnson Mason and George Ellis began manufacturing straw bonnets in what later became known as the Lowell Mason house. The manufacture of hats became the principal industry of the town until well into the 1950s. At its height, the E.V. Mitchell Hat Factory was the second largest straw and felt hat factory in the country, employing over 1,000 workers—more than the population of the town itself. Workers came from as far away as Maine and Canada to work at the North Street plant.

Other small industries included a manufacturer of cut nails, a fork factory, a company for the manufacture of boots, a wire factory, a box factory and a substantial company manufacturing horse-drawn carriages. Known as Baker-Cushman Carriage, the carriages made there were sold throughout New England.

Throughout this time most of Medfield’s population growth was by natural increase. Small numbers of Irish immigrants came here in the 1850s to work as maids in Medfield homes and a small number would continue to enter the town into the 20th century. Italian immigrants came in a shorter span of time from the early 1900s into the 1920s and settled along Frairy Street.

The Civil War

The people of Medfield prepared to fight in the Civil War with the same patriotic fervor that was seen here during the Revolutionary War. Over 82 men served in the Army and Navy and 14 men gave their lives for the preservation of the Union. Noted abolitionist Ellis Allen lived here at 260 North Street, and his house and barn became one of the prime stops on the Underground Railroad.

19th Century Transportation

In 1806 the Hartford and Dedham Turnpike was established, and its stagecoaches stopped at Clark’s Tavern, next door to the Peak House. The stage route through Medfield was known as the Middle Post Road, but the Upper Post Road through Sudbury was preferred by travelers because it provided better taverns. The first train of passenger cars came to Medfield in August of 1861, and ran from Medfield to Boston.

In 1806 the Hartford and Dedham Turnpike was established, and its stagecoaches stopped at Clark’s Tavern, next door to the Peak House. The stage route through Medfield was known as the Middle Post Road, but the Upper Post Road through Sudbury was preferred by travelers because it provided better taverns. The first train of passenger cars came to Medfield in August of 1861, and ran from Medfield to Boston.

By 1870, trains also commenced running on the Framingham & Mansfield railroad. The junction of the two lines, off Adams and West Mill Street, became an important “Junction” train station for Medfield residents. The trolley was here, running from Dedham through Medfield to Medway, Franklin, Mendon and points west, from 1899 until it was put out of business by the automobile in 1924.

The 20th Century

At the time of the 250th anniversary in 1901, Medfield was still a lovely village with green fields, lush meadows and winding rivers. Medfield had grown to 1,600 residents, not counting the residents at the state hospital. It was a typical New England town consisting of 335 dwellings. A tax rate of 1.1 percent based on town-wide valuation of $1,454,265 met the appropriated obligation of $17,347. Education had the highest share of the town budget: $5,375.

At the time of the 250th anniversary in 1901, Medfield was still a lovely village with green fields, lush meadows and winding rivers. Medfield had grown to 1,600 residents, not counting the residents at the state hospital. It was a typical New England town consisting of 335 dwellings. A tax rate of 1.1 percent based on town-wide valuation of $1,454,265 met the appropriated obligation of $17,347. Education had the highest share of the town budget: $5,375.

Medfield had three public schools. The Centre School, later named the Ralph Wheelock School, held all grades and served the village area of town. The Lowell Mason School at the corner of North and School Streets, generally holding grades 1 through 6, served the North District, and the Hannah Adams School at the corner of High and South Streets, also generally holding grades 1 through 6, served the South District. Medfield High School was first officially established on March 24, 1870, and was housed in the Centre School/Ralph Wheelock School on Pleasant Street, until the building burned down in 1940.

Long before the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920, Medfield encouraged the voting rights of women. In 1900, seven women paid a poll tax and qualified to vote in local elections. As early as 1881, women voted for the school committee and by 1916 women were permitted to serve as members of the school committee, as trustees of the public library and as overseers of the poor. When the state constitution was amended to conform to the Federal law, 48 of the 381 votes were cast by women.

In 1900 the importance of farming was reflected in personal property taxes, which were levied on 431 cows, 64 other cattle, 31 swine, 1,637 fowl and 256 horses. Associated trades and small industry, such as three sawmills and slaughterhouses, a tannery and two cider mills, were flourishing trades.

The 20th century also saw buses and automobiles begin to replace steam and electric trains. The town sold its electric company in 1906 to the Boston Electric Illuminating Company, and in 1921 the town took over the operation of the Medfield Water Company. In 1924, the town established a Planning Board to prevent haphazard growth. That same year the Peak House was restored.

Medfield’s sons and daughters participated in spirit and large numbers in both World War I and II. Eight Medfield men lost their lives in World I and ten in World War II. Following WWII, thanks in part to the GI Bill, large numbers of homes were built and then bought by young families. Medfield’s first subdivision was begun in 1948 in the Summer Street and Pine Street area. The large families that followed swelled the enrollment in the schools, causing new schools to be built. The housing boom continued into the 1970s, giving the town a more suburban look.

Conservation Movement

Attempts to conserve green areas came with the establishment of the Conservation Commission in 1962. In 1964, a Master Plan was undertaken to plan for projected growth. Medfield has continued to grow into a desirable, residential suburb. New subdivisions are developed in a controlled fashion and industrially zoned land has been limited to clean light industry.

Attempts to conserve green areas came with the establishment of the Conservation Commission in 1962. In 1964, a Master Plan was undertaken to plan for projected growth. Medfield has continued to grow into a desirable, residential suburb. New subdivisions are developed in a controlled fashion and industrially zoned land has been limited to clean light industry.

Today this beautiful, unspoiled area of conservation land, forest, ponds and streams is an invaluable resource for the town of Medfield. In preserving the land, the town also saved tenfold its investment against what the cost of town services would have been, and future generations will reap the benefits of that far-sighted action.

The year 1977 may well be regarded as a landmark year for conservation in Medfield. The Conservation Commission and town voters supported Congressional action turning over the wetlands all along the Charles River to the U.S. Government for a Natural Valley Storage to ensure that our major wetlands are never filled in. This area serves as a vast sponge to store water in the spring and during storms, reducing the possibility of flood damage in Boston and saving the Massachusetts taxpayers great expense in not having to build a dam in the lower Charles River area.

Agreements worked out guaranteed the town direct control over its recreational use. The protected area includes 75 percent of all existing wetlands in the Charles River watershed. Protection of the Charles River wetlands has provided numerous additional benefits to communities like Medfield throughout the basin. Without protection, the Corps estimated that 40 percent of all existing wetlands at the time would have been lost to development by 1990.

Medfield Today

Medfield in the 21st century remains a desirable residential community that continues to draw people to the town based on its renowned school system and its still rural character. The Trustees of Reservations, a nonprofit land conservation and historic organization dedicated to preserving natural and historical places in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, owns several large parcels of property in Medfield including Rocky Woods, Noon Hill and the Rhododendron Reservation (known by locals as the Rhododendron Swamp). Large amounts of land, especially in the Noon Hill and Charles River areas, have been permanently protected from development. The historic homes and open space with natural beauty continue to give the town that special quality that locals say is what makes Medfield, Medfield.