Jun 1, 2025

In Part 1 of this story, I wrote that I was thrilled to be able to read, touch, and hold some of the letters of Civil War soldier Eben Granville Babcock III (1843-1917). As I begin Part 2, I wish to reiterate that this is meant as a human story, not written by an expert in battles and troop movements; I am learning as I go, and loving every moment of it. This young man’s growth, concern for his family, and longing for home are more interesting to me than encyclopedic facts. I frequently stop to research as I go through these letters, and the more I know, the more there is to learn.

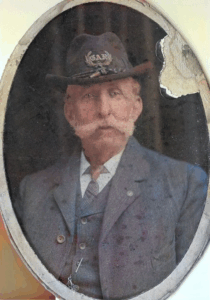

Babcock was one of twenty-nine Medfield men who answered President Lincoln’s call for 15,000 men to enlist in the Union Army in 1862. Part 1 tells of his earlier experiences as a soldier, as told through letters to his mother, Mary Whitney Babcock. We will return to these later in this article, but let us not overlook the one surviving letter to his father (especially so close to Father’s Day). Ebenezer Giles Babcock (1793-1876) was a farmer, and at the time of this letter he was 71 years old, his son 19. Ebenezer and Mary had eight children, of whom Eben was the seventh; only three-year old Annie remained at home on Pleasant Street in Medfield. As a reader, I was struck by the difference between this one letter to Father and the several letters to Mother. I would say the young Babcock seems much less comfortable in conversation with his father. The tone is deferential due to his father’s age; the word choice more formal, the subject matter limited to farming, fishing and the weather. Even the handwriting is different from the letters to Mary, with carefully-formed letters done in ink rather than blunt pencil, as if the son felt the need to make this letter more legible than most. It is touching to read the young man’s hope that his father will still be there when he gets home.

I Wish I was at Home to Help You Plant and Get the Hay

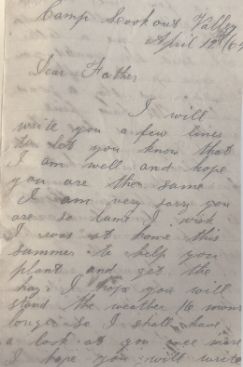

Camp Lookout Valley, April 12th 64:

Dear Father,

I will write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope you are the same. I am very sorry you are so lame, I wish I was at home this summer to help you plant and get the hay. I hope you will stand the weather 16 months longer so I shall have a look at you once more. I hope you will write me a few lines in the next letter mother sends. Abby wrote me a letter and said she wanted you to come up there after planting and stay a good while. We have fine weather around here, the peach & pear trees are all in bloom and what farmers there is (sic) around here are planting. There is some fine land around here for corn and potatoes, especially along the banks of the Tennessee River. It is about a mile from the camp to the river. It is a good deal longer than the Charles River. The band went a fishing (sic) in it the other day, caught some pout and white perch, the pouts were very large and whiter than any I ever caught. I don’t think of any news to write so I will close now. Tell Annie I am very much obliged to her for the Almanac but I can’t understand it yet.

From your Affectionate son, E. Granville Babcock

I Told Them to Write to the Selectmen Immediately; Cheer Up; Two Fine Hens

While the soldier’s story gets a bit more color from the father’s letter, it is really the mother’s letters that carry the story. We know that Eben was honorably discharged, but his military career nearly took a troublesome detour, and he turned to Mary – and the Medfield Board of Selectmen! – to straighten things out. Our collection of letters includes one from the Adjutant General’s Office of Massachusetts to Mary Babcock, part of some ongoing correspondence about a major error on the Army’s part: Eben had been erroneously counted as a deserter on June 19, 1863. On November 30, a Mr. Nehemiah Brown wrote to acknowledge that Mary had sent in some exculpatory evidence on her son’s behalf; “I have written to the Commanding Officer giving him the facts which you stated in your letter, and asking him to correct his rolls. As soon as he does so, I will issue a certificate of the fact.” Eben himself seems to take this undoubtedly stressful situation in stride and with good humor, writing to Mary on November 21, “I received another letter from (illegible) Infantry today, so I wrote…to the Captain and set it straight. I told him to write to the Selectmen immediately…well you haven’t seen me home yet have you?” (Note: In 1863, the Medfield Selectmen were Benjamin Shumway, George M. Smith, and Jeremiah R. Smith.)

It is so easy to relate to the young man’s anguish about disappointing his mother, telling her he might get a furlough but he might not. Continuing with this letter, Eben writes,

“there have been some new arrangements since I wrote. We are going into Patterson’s Fork into barracks and all them that belong to the Army of the Potomac are going to their regiments and they say we won’t get a furlough until we get there. I won’t write any more about it until you see me, for I might disappoint you. I know I have now. Don’t be discouraged, cheer up and keep your eyes open. I give my love to all the folks and to Father and Annie. When you get the allotment you send me some or the next time you write if you can. I spent a half dollar out of the 2 for to get my boots taped (sic). I was out the other evening and we got two fine hens, carried them to our tent, kept them till morning then we took them over to Mrs. B___, a woman that we got acquainted with and she baked them and stuffed them and we had them for supper…She is a nice woman I tell you, she said any time we get some fowls to bring them to her and she will cook them. She is a splendid cook I tell you, we carried her two of our loaves of bread to stuff them with (sic). I hope you will get the allotment and I hope I shall get the furlough but I can’t tell yet. I had not ought to said (sic) anything to you about it had I. Write soon as you get this, won’t you. I hope you won’t be disappointed. Send me some money if you can and I will save it if I come home to pay my fare and get something to eat on the road. I have got a little now but not enough. Love to all and take a lot for yourself and dear little Annie. From your son E.G. Babcock/in haste.

Note: The Allotment Commission was established by Congress on December 24, 1861. The idea behind this voluntary program was that one-third of a soldier’s pay was to be sent home, in order to prevent wasteful spending among soldiers during their off-duty time. Eben had opted into this program, and wanted to be sure that his family was receiving the allotments.

1864: In Sight of Atlanta; Don’t Believe the Newspapers; What I Want Most

Eben and the 33rd Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers were close to Atlanta by July of 1864. Eben makes a point of telling Mary that the news she receives from the papers is false, which I find fascinating, but time does not allow me to examine the particulars about Generals Hooker and Sherman. My admittedly rudimentary research has only made me want to know more.

Camp 33rd Reg. Mass Volunteers, July 10 1864

Dear Mother,

I received your letter of June 24th today and was very glad to hear from you once more. I am well and hope you and Annie are the same. We are laying in camp now and have been for the last three days . We are about a mile and a half from the river and in sight of Atlanta although it is some 9 or 10 miles from where we lay. The rebels have all retreated across the river and our pickets are advanced on to the rivers. . . About Gen. Hooker getting wounded and Gen. Sherman getting whipped, it is all false, he has not been repulsed since we started on this campaign that we have heard of. They have charged our breastworks a number of times but had to go back double quick with great loss. One night the first division of our corps was charged upon by the rebs with four lines of battle and 24 pieces of artillery opened on them and completely cut the first and second line of battle to pieces. They buried 240 in the morning after the fight of rebs and they were burying all night besides. Don’t believe all the papers state for if they tell such stuff it ain’t true. It is pretty warm here now but I get along pretty well. I have enough to eat now, we have (illegible) the railroad as far as Marietta, about two miles from where we now lay. The most I want is a piece of tobacco. I can’t get any of that because it is very scarce. Send me a piece in a newspaper, it won’t cost much if you see to have the postmaster weigh it before you start it off. Well, I must finish off with giving my love to father, Annie, yourself and all the rest. No more at present.

Your affectionate son, E. Granville Babcock.

The third and final part of this series will look at the rest of Eben’s letters from 1864 and 1865, as well as searching our archives for information about his life back in Medfield, after the war.