April 1, 2023

Portal readers of a certain vintage will recall 20 or 30 years ago a delightful annual fall fundraiser called the “Emperor Onion Fair” at the venerable Unitarian Universalist church.

It begs the question, what or who was the Emperor Onion?

It was not a vegetable of the genus Allium.

Charles “Emperor” Onion (1796-1852), was the most colorful – and perhaps to some, the most exasperating – character in Medfield’s history.

His father, David Onion, moved from Dedham to Medfield in the 1770s and served in the Revolutionary War. The first Onion (maybe O’Nion) probably came to Dedham during the Great Migration of the 1630s. David Onion, a carpenter, bought a house at the corner of South and Main Streets, now the site of Brothers.

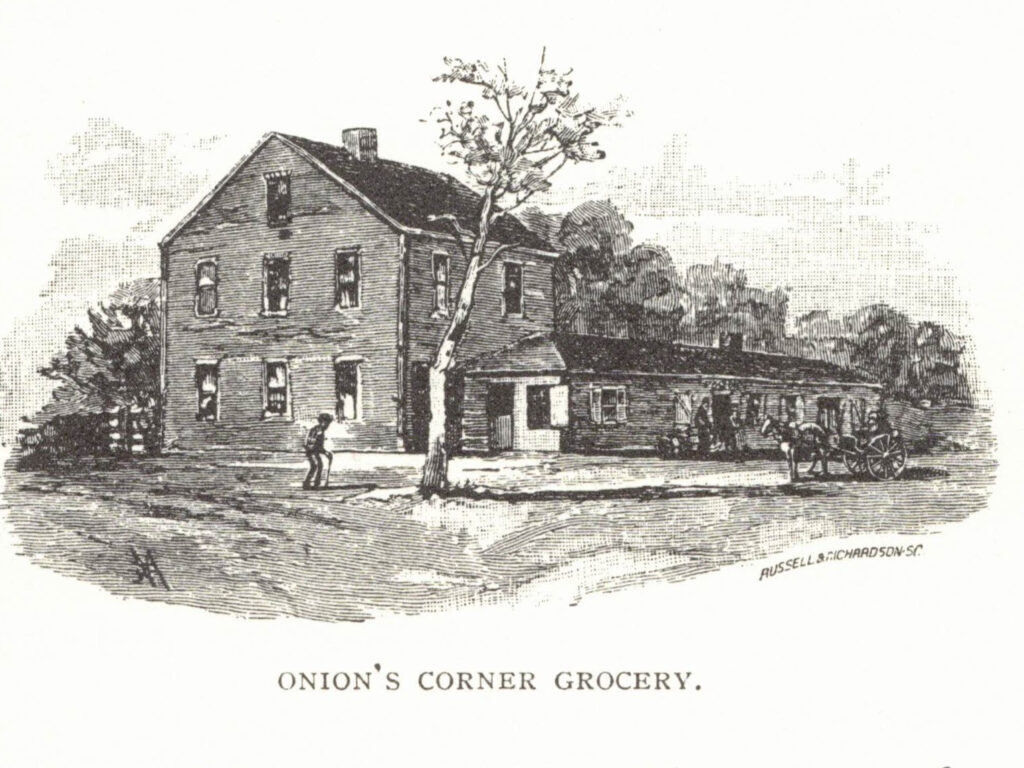

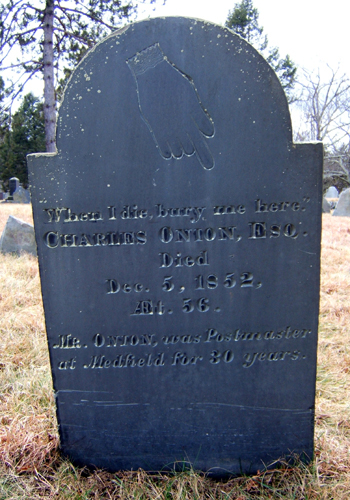

Charles was originally said to be a watchmaker, who briefly had a shop across the street, where the Baptist church now is. He was postmaster from 1823 to 1852, and in the 1820s and 30s he operated a general store in the building that had been his father’s house.

Medfield historian William S. Tilden (1836-1912) wrote in an unpublished manuscript,

“Onion was a single man, having with him his aged mother, his only near relative.

“The store fronted on Main Street and was a one-story building, long and narrow, about 45 by 18, painted yellow, with wooden shutters.

“The end next to South Street, on which a door opened also, was devoted to clothes, calicos, shoes, and the common assortment of dry goods.

“The middle of the building, with a door opening on Main Street, contained the post office, desk, groceries, candy, tobacco, hardware, and knick-knacks in general.

“The westerly end was the back store, a place for molasses hogsheads, flour, codfish, and the heavier articles of a West India goods store of the period. At the west end (i.e., the side closer to Pleasant Street) of the store there stood a shed for horses.

“The middle part of the store, where people came for their mail, contained the stove, and around it were seats built in which furnished the general lounging place for the villagers, to which not only some trifling business, but Mr. Onion’s peculiarities and maudlin wit attracted them. This was the old-time country store, such as we see in pictures.”

From Tilden’s writings, and because Onion lived a relatively short life, one can infer that Onion had a drinking problem. In the 18th and 19th centuries, alcoholism was a much more severe problem than even today. It was viewed as a moral failing more than a disease, and a century of intense temperance advocacy led to Prohibition in 1920. Thomas Jefferson built Monticello but repeatedly tore down and rebuilt it over a period of 40 years. He hired and fired the same alcoholic mason countless times – but Jefferson kept rehiring him because, when sober, he was the only one capable to doing the work satisfactorily.

Tilden continues, “Mr. Onion was feeble in body as he came to middle life, and his habits were such as unfitted him for carrying on business. In 1837 two brothers, Joseph and Thomas Barney, took the store and conducted the business, Mr. Onion retaining a nominal interest in it. At his death, the property passed into their hands.

“The old store was finally cut in two. The easterly end forms the ell part of the double tenement house before mentioned, and the other was removed to Barneyville.” Barneyville referred to a section of Curve Street, but recent research failed to determine exactly where the house was sited and whether it is still standing.

In another manuscript, Tilden explains the “Emperor” title:

“Sixty years ago, or thereabouts, (about 1830) a visitor in our village would have been surprised at the titled dignitaries we had with us, certain of our citizens being in common speech embellished with these honors. There were the “Pope,” the “Alderman,” the “Marshal,” the “Count,” etc. Charles Onion, watchmaker, town clerk, storekeeper and post master, was known throughout this region as the “Emperor,” — sometimes “Charles I, Emperor of Medfield.”

“How he came by the title is unknown, whether he in his communications assumed the Napoleonic, and so acquired the distinction from his friends, or whether he adopted that style after being nicknamed so as to carry out the joke, we cannot tell. Certain it is that many of his letters were remarkable productions.

“His store and the post office, which he kept for thirty years, was on the corner of South and Main Streets. Though injured by dissipation, he was naturally a very witty man, as well as unique a person not easily described. For many years his place of business was a point where congenial spirits and lovers of hilarity, from this and other towns, gathered daily, and many were the practical jokes and “scrapes,” as they were called, that originated there.

“Wales Plimpton, the old sexton, who lived opposite the cemetery, had a pear tree on his farm that bore the vilest wild pears conceivable. No use was ever made of them; they were as hard as stones, never mellowed, were intensely sour and bitter, and puckery to the last degree.

“One day, a young fellow named Al Smith, (greatly given to taking sustenance insomuch that his own father said of him, “It makes him hungry and dry to eat and drink”), not knowing the character of the fruit, was going by, and was seen to go over to get some of those pears.

“This suggested fun for the Emperor. A man was sent as sheriff to arrest Smith and bring him before a court for trial. Meantime several persons had assembled at the store; specimens of the fruit were brought in, witnesses were summoned, and a jury empaneled, the Emperor himself being judge, and conducting the proceedings.

“The prisoner was identified, the testimony duly given, the case given to the jury, who presently brought in a verdict of guilty.

“The Emperor, as judge, now pronounced sentence. He said that guilt was proved, and the charge sustained. It was a serious breach of law, this going upon a man’s estate and removing his property; in fact, a state prison offense. He was moved therefore to make the penalty a very serious one, which was this: – the prisoner was to eat, then and there, six of those pears.

“Smith, somewhat frightened at the august proceedings, commenced at once upon service his sentence. With great labor he finally worried down one of his pears; and as soon as he could get his mouth into shape to speak, he requested a commutation of his sentence, saying he’d rather go to the state prison than eat the other five.”