Nov 1, 2024

On a Saturday evening in December of 1912, Dr. Karl Muck, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, awaited the arrival of a most important patron. He had learned during his tenure that he could not commence the evening’s program until Mrs. Isabella Stewart Gardner occupied her customary seat. Even Dr. Muck, a friend of Mrs. Gardner, could not have imagined what he, his orchestra, and the audience were about to witness on this evening. Striding into Symphony Hall, a white band with red letters declaring “Oh, You Red Sox!”, wrapped around her head, Mrs. Isabella Stewart Gardner proclaimed her adoration for the Boston Red Sox and celebrated her team’s triumph over the New York Giants in the 1912 World Series. The Town Topics reported:

“It looks as if the woman had gone crazy. With this band bound like a fillet around her auburn hair, she appeared in her conspicuous seat at a recent Saturday night Symphony Concert, almost causing a panic among those in the audience who discovered the ornamentation, and even for a moment upsetting Dr. Muck’s men so that their startled eyes wandered from their music stands.[1]”

In 1912 Mrs. Gardner was 72 years old, and she continued to draw attention to herself and shock Boston society.

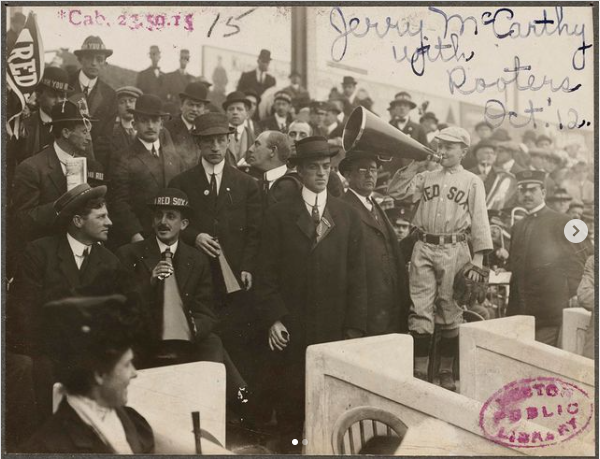

In Boston’s Royal Rooters, Peter J. Nash states that the band around Mrs. Gardner’s head was a Royal Rooter sash, emblazoned with the words “Oh, You Red Sox!”, taken from the title of a popular song written and composed by George P. and Ellen Ashworth for the 1912 season. The Royal Rooters, led by Michael T. “Nuf-Ced” Mcgreevy and Boston mayor John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, raucously supported the home team and crudely challenged the opponent, whether in Boston or away. Whether or not Mrs. Gardner’s head band was a Royal Rooter sash, a Royal Rooter head band, or a cloth with her own handwritten letters remains moot, and although the fine details of the evening’s event may remain nebulous, she did indeed arrive at the symphony as described above.

A photograph, possibly of the South End Grounds in Boston, found in her personal belongings shows early fascination with baseball. This photograph, which she may have taken herself, includes the notation “Base-ball Play Boston June 1898.” She regularly attended baseball games and when the Boston American Baseball Club became the Boston Red Sox in 1908[2] she attached herself to that team. Her loyalty remained steadfast and, when Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox, opened in 1912, she bought a season ticket. Her residence and museum, which opened in 1903, was approximately one-half mile from the home of her beloved team.

Isabella Stewart was born on April 14, 1840, in New York City. She was the first of four children born to David and Adelia [Smith] Stewart. Although often reminded that she was not a true blue blood, that her maternal grandfather had been a tavern owner, Isabella enjoyed the benefits of prosperity. David Stewart had accumulated wealth through the manufacture and sale of linen and, later, through mining investments. Her family’s financial resources, and her parents’ wishes, provided young Isabella with a private education in New York City and Paris. While attending a French Protestant school in Paris she befriended Julia Gardner, daughter of John Lowell Gardner Sr., of the affluent Boston Brahmin Gardners. Despite Isabella’s occasionally unsettling behaviors (casually flirting with one of her teachers – the Italian teacher – in Paris, for example)[3] Julia and Isabella remained friends; and it was Julia who introduced Isabella to her brother (and future husband) John Lowell Gardner, Jr. in 1858.

Isabella Stewart was born on April 14, 1840, in New York City. She was the first of four children born to David and Adelia [Smith] Stewart. Although often reminded that she was not a true blue blood, that her maternal grandfather had been a tavern owner, Isabella enjoyed the benefits of prosperity. David Stewart had accumulated wealth through the manufacture and sale of linen and, later, through mining investments. Her family’s financial resources, and her parents’ wishes, provided young Isabella with a private education in New York City and Paris. While attending a French Protestant school in Paris she befriended Julia Gardner, daughter of John Lowell Gardner Sr., of the affluent Boston Brahmin Gardners. Despite Isabella’s occasionally unsettling behaviors (casually flirting with one of her teachers – the Italian teacher – in Paris, for example)[3] Julia and Isabella remained friends; and it was Julia who introduced Isabella to her brother (and future husband) John Lowell Gardner, Jr. in 1858.

Isabella reflected traits of her paternal grandmother, Isabella Tod Stewart – not beautiful, but physically energetic and adventurous, trimly elegant, commanding and demanding attention.[4] Isabella evinced qualities that appealed to men (her fine skin and lovely figure) and behaviors that troubled women (her presumed immodesty in dress and manner). However, mesmerized by her charms, John Lowell Gardner proposed to Isabella, and they were married on April 10, 1860, in New York City. Soon thereafter, the couple moved to Beacon Hill in Boston, Massachusetts. She had entered “Cold Roast Boston” and “Boston Brahmin” Society.

In his 1861 novel Elsie Venner, native Bostonian Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. coined the phrase “Boston Brahmin” – a means to describe the wealthy, educated, and elite class of Boston society of the nineteenth century. Also at this time, another Boston native, writer and artist Thomas Gold Appleton, used the phrase “Cold Roast Boston” in reference to the Boston Brahmins’ parsimonious ritual of serving hot roast beef on Sundays, and leftover cold roast beef on Mondays. As these epithets appeared, the immigrant population of Boston grew, and a very clear class structure evolved with Boston’s Brahmins at the top. This is the established social milieu into which Isabella Stewart stepped.

John Lowell Gardner adored his young wife and his family welcomed her. Yet Isabella found her role as the wife of a well-to-do Bostonian challenging. Unwritten yet very real societal expectations constrained her. The outgoing woman of New York City and Paris now seemed shy (ironic considering the woman she would become). Belle, as she came to be known at this time, sought escape from the rigidity of her newfound social status. She loved to attend balls and was known to dance, with numerous male admirers, for hours on end. Also, her father-in-law enjoyed her company on morning horseback rides on the grounds of the family’s Brookline, Massachusetts estate. Still, stress, induced in part by the fact that her sisters-in-law, Julia and Harriet, had already given birth to sons, affected her deeply. She became weak emotionally and physically and appeared small and frail; her husband was seen carrying his exhausted wife into their Beacon Hill residence. However, 1862 saw her body and spirit reawaken when she became pregnant with her son. John Lowell Gardner III was born on June 18, 1863. For nearly two years, Isabella and her husband engaged joyfully in parenting.

Their joy was short lived. John III was not even two years old when he contracted pneumonia and, on March 15, 1865, died. Around the same time, Isabella suffered a miscarriage and learned that she could no longer conceive. As she sank again into mental, emotional, and physical darkness, her doctor, the famed physician Henry J. Bigelow, recommended that her husband take her on an extended journey abroad. It happened that Dr. Bigelow, in addition to being a fine medical man, was one of Isabella’s admirers. He wanted the best for Mrs. Gardner. The Gardners followed the doctor’s recommendation, and their subsequent travels would awaken Isabella’s vitality.

Their first travels abroad, in 1867, took them to seven countries. With the support of her devoted husband Isabella experienced new adventures, observed different cultures, embarked on bold treks, enjoyed the company of fellow travelers, reveled in extraordinary challenges, and began her remarkable career in art and artifact collecting. She developed an independent spirit, a free-thinking manner, a joy in companionship, and an unmatched loyalty to her family, her friends, and her personal interests. She would maintain these traits for the rest of her life, in every aspect of her life.

Isabella enjoyed activities, her own, and those of others. Her interest in art and the acquisition of art became a passion and a competition. Art with its multifarious forms and aspects enthralled her. Her love for and support of artists, musicians, writers, dancers, and athletes evolved into her life’s purpose.

On Isabella’s return to Boston in 1868, Brahmin society, and indeed all of Boston, felt her presence. No longer the infirm patient, Mrs. Gardner became a charismatic figure with a keen mind and a strong will. Her critics (mostly women) said her Parisian tailored clothing – the design of Charles Frederick Worth – revealed too much flesh; her behaviors had become too scandalous. People impugned her “chandeliering”[5] at balls and her pleasure in the company of countless male – young and old – admirers. Women feared that their husbands, sons, and other male relations would hear Donna Bella’s (another name for Mrs. Gardner) siren song and become a member of what came to be called “Isabella Club.”[6]

The stories and the gossip, often inaccurate, flowed in torrents. However, she seemed to enjoy the attention given her and was known to say, “Don’t spoil a good story by telling the truth?”[7] Her sense of responsibility (art collecting and mentorship), her loyalty (family and friends), and her notion of fate (her museum) motivated her and allowed her to remain apart from all gossip and scandal. Boston society soon began to revolve around her and strove to witness and partake in her every action. Indeed, as Wanda M. Corn has noted, “Boston newspapers regularly commented on her charms and her pranks, and one reporter, almost always cited in any story about Gardner, went so far as to claim that ‘All Boston is divided into two parts, of which one follows science, and the other Mrs. Jack Gardner’.”[8]

Already wealthy in marriage, Isabella inherited funds from her father, who died on May 17, 1891. Her three siblings had predeceased her, so she was sole heiress to a large fortune, two million dollars.[9] On December 10, 1898, Isabella’s devoted husband died. This event did not, as previous tragedies had, bring her into depression. Rather, love for and dedication to her husband urged her to fulfill their mutual dream of building a public art museum; and she now had resources to realize this goal. She could now live by her own words: “Let us aim awfully high. If you don’t aim, you can’t get there.”[10]

Before John died, he and Isabella had purchased land in Boston’s Fenway, a portion of the Emerald Necklace, a green space planned by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Here she would build her own Venetian Palazzo Barbaro. Here she would live, display her art, and startle Boston. Her museum opened in January of 1903 (incidentally, the year of the first World Series, which happened to be played in Boston). Friends were treated to a concert performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and to a reception at which, as the tale is told, “champagne and donuts” were served. The museum was opened to the public in February of 1903, and all visitors were advised to follow precise instructions regarding behavior. Mrs. Gardner herself monitored the visitors.

Isabella, now also known as Mrs. Jack, had become a true patron of the arts and athletics. She willingly and joyfully accepted her role as both mentor and muse for a select group of artists, writers, musicians, and athletes. She attached herself to the likes of writer Henry James, painter John Singer Sargent, art collector/buyer Bernard Berenson, musician/composer Charles Loeffler, professional boxer John L. Sullivan, and Harvard College Football Coach Percy Haughton.

As she was mentor and muse, she truly believed that she was a mascot for athletic teams – be it the cricketers of the Boston Athletic Association, the Harvard Football team, or the Boston Red Sox. “When the Red sox of Boston played the Giants of New York in the World’s Championship Series of 1912, she happened to invite a very unintelligent friend to the opening game; as it was won by the local team, she insisted that the same friend must go with her to every game, in order not to change the luck. The Red Sox won the series.” [11]Sports and athletics of all types appealed to her. An incident which has the makings of a Gardner tall tale has been recounted by Edward Sheehan, a boxing referee who acted as promoter for “Mrs. Gardner’s Private Bout,”[12] a boxing match in one of her salons. Sheean describes the bout:

“The fight was held about two in the afternoon [in an artist’s] studio…The place was full of paintings and statuary…Mrs. Gardner wanted the whole show and she got it all right – yes, it was Mrs. Jack who put up the money. Well, it was one strange fight. I was used to all sorts of crowds, but I never saw a fight crowd like that before. When all those sedate-looking, quietly dressed women came into the studio, I confess I had my misgivings. Did they know what they were in for, or did they have an idea that a prize fight was like a game of Ping-Pong? Would they scream and faint when some one got a sock in the jaw, and a little blood splattered around? I didn’t know…but I had an idea that come what might, Mrs. Gardner would stick by the ship, because she had a reputation as a dead game sport. I didn’t need to worry any…they were impartial in their applause, cheering either fighter when he socked a good one home. Mrs. Jack seemed to have a liking for Harrington – he was a good looking fellow and won the bout – but after the fight she took pains to compliment [the loser] Doherty on his stand. The fight lasted 17 rounds.[13]”

Isabella appreciated physical prowess and enjoyed the aesthetics of athleticism. She once had her friends over when Eugen Sandow, a celebrated bodybuilder, was visiting was there; they were invited to stroke his biceps!

She loved to witness and participate in competition. The acquisition of art became her competition. She thought very highly of winning, but did not wish to revel in losses and is known to have said “Win as though you were used to it and lose as if you liked it.”[14] Her sporting interests extended to horseracing. Winnings through her own racehorse, Halton, permitted her to acquire the painting Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua by Polidoro Lanzani.[15]

Already accustomed to unpredictable actions, her family and friends were not surprised when Isabella would “drag” people with her to baseball games. The actor and humorist, Robert Benchley, attended games with Mrs. Jack and he noted that she “loudly encouraged all the Boston players by name.”[16] One tale suggests that Benchley, while employed at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, was actually asked to attend the games with Mrs. Gardner to deter her from asking other employees to join her.

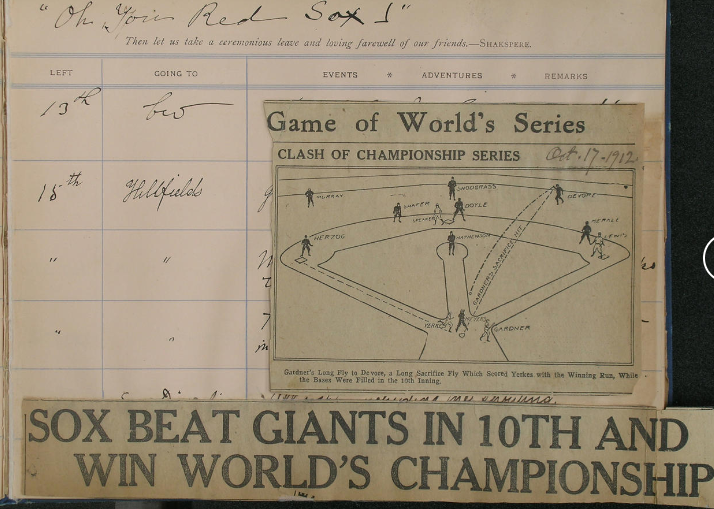

Mrs. Gardner destroyed many of her own letters, and often asked her correspondents to do the same. However, she did keep guest books, replete with signatures of and comments from her numerous visitors. In addition to expressions of gratitude, witty and playful remarks, and even academic proclamations, these guest books contain specific references to sports. She took great pleasure in citing, and describing in her own hand, the athletic achievements of her great nephew George Peabody Gardner, the first Harvard man to be awarded 11 varsity letters. He played baseball, football, hockey, tennis, and participated in track and field. Photos of George with his teammates or in action on the playing field fill her guest books. Other comments, often accompanied by newspaper clippings, include reference to boxing matches (Jack Johnson over Jim Jeffries), tennis matches (nephew George), horse racing (Halton), crew races (Harvard vs. Yale), aviation (Claude Grahame-White), and of course baseball (Boston Red Sox). Regarding baseball, and specifically the Red Sox, one outstanding entry in 1912 includes her own notation “Oh You Red Sox” atop a newspaper clipping which she pasted into her guest book. It was not long after this particular entry that she made her memorable entrance at the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Mrs. Jack’s affinity for the arts often led to unplanned philanthropy and compassion. Charles Martin Loeffler, violinist and composer, often performed for Mrs. Gardner, who truly delighted in his music. After he married the wealthy Elise Fay in 1910 Loeffler found more opportunity for pleasures such as “training the boys’ choir at the church in Medfield.

“He brought his boys to Fenway Court to sing for Mrs. Gardner, who was thrilled by the music and impressed by the faultless performance. But she proceeded to make friends with the boys afterwords and discovered that they wanted uniforms for their baseball team. She told Loeffler to get some and send her the bill. Loeffler’s letter to Mrs. Gardner describes his difficulties. He went to a ‘regular clothier,’ not knowing any better. They scornfully directed him to ‘the Iver Johnson Sporting Goods Company and Wright and Ditson’ – establishments of which he had never heard. It was all ‘a matter in which I am inexperienced,’ he wrote plaintively. Then came the bewildering question of assorted sizes for little boys. Ivers Johnson agreed to take back suits that didn’t fit. At last ‘the B.B. suits’ finally arrived. The boys were delighted and ‘expected to play the Dedhamites.’ Then it rained! Loeffler wrote that he was going to give his choirboys ‘a good sound rehearsal of the ‘Dies Irae,’’ since they could not go out and play ball.”[17]”

It happened that one of her protégées, the melancholy artist Dennis Bunker, also lived in Medfield. He once said, in a moment of distraction “It is a mistake to have only one life…We ought to be given three tries like the baseball men.”[18] Although many gossips wanted society to believe that Mrs. Gardner enjoyed only the company of young men, they were disheartened as she associated with women artists (Sarah Whitman), dancers (Ruth St. Denis), composers (Clara Kathleen Rogers), and singers (Nellie Melba). Ruth St. Denis danced, at Fenway Court, her “‘Radha,’ inspired by Hindu dance movements.”[19] Newspapers reported that “‘Cold Roast’ Boston sat up and took notice…and rubbed its eyes at the spectacle of a barelegged maiden who put the Persian dancers on the midway to shame…”[20] Again, she enjoyed shocking those around her, while celebrating physicality and form – this time female.

“Where did they get their moxie?” Wanda Corn asks referring to the likes of Jane Stanford, Alice Pike Barney, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and Isabella Stewart Gardner, each of whom imagined and created remarkable art collections. The question seems particularly apt in the case of Mrs. Gardner given her verve and assertiveness, and because Moxie, a Boston based soft drink introduced in the late nineteenth century, became linked with Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox. She “spurned ‘fossilized conventions’ of the day”[21] and had she been “confined within the narrow limits of their [Brahmins] conventionalities, if her free spirit had known their inhibitions, her genius might never have flowed.”[22]

In his biography Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court, Morris Carter notes that Isabella was always interested in sports and, in addition to her own athletic abilities, “took the keenest delight in all athletic contests.”[23] He also states that “although she was a good loser, she loved success.”[24] She could and did apply these affinities and philosophies to her own life and to those whose lives she touched. She embraced her role as muse and mentor, believed in her association with athletes and athletic competition. And this she did with moxie, enjoying the competition while honoring her family, friends and teams.

With age, she confronted physical challenges, including breaking her leg in 1916. Frustrated, she wrote to Bernard Berenson: “…the doctor forbids any crowd. I couldn’t even see the great [World Series] games. But I can always go and look at those wonderful stone carvings you got for me…” She accepted, in 1922, John Singer Sargent’s offer to paint yet another portrait of her (he had painted a most notable portrait 1888). Mrs. Gardner in White is one of Sargent’s finest works and suits the conclusion of Mrs. Gardner’s extraordinary life. Although hampered by a series of strokes, the first in 1919, she persisted, until her death on July 17, 1924, in fulfilling her destiny.

The Gardner tall tales are many and varied, and some are even true – she did host athletic contests at Fenway Court, and she did walk a lion at the zoo in Boston. However, one very real truth remains: Isabella Stewart Gardner was a woman of physical, mental, and spiritual depth who visualized and created a museum. The Gardner Museum is testament to this remarkable woman who, late in life, feared that she would not have enough financial resources to keep the museum afloat. In her waning years she appeared miserly, but she understood that financial endowment for a public museum must be firm.

Okaura-Kakuzo, Japanese philosopher, poet, artist, and appointed staff member of the Museum of Fine Arts was “…a man with just the range Isabella [Stewart] Gardner liked, proficient in all the expected refinements of a Japanese gentleman, mental and physical, from poetry writing and flower arranging to fencing and jujitsu.”[25] (Mrs. Gardner herself learned jujitsu before her travels to Spain in 1906). She met him in 1904, she 64 years of age and he 41. In 1905, Okakura wrote “The Stairway of Jade,” a tribute to Mrs. Gardner’s lovely museum and her splendid genius. He called her The Presence alluding to a sense that she was and would always be within Fenway Court.

Mrs. Gardner’s dynamic influence and presence remain within the Gardner Museum. The courtyard of her Palazzo Barbaro celebrates art and reveals, perhaps, her sense of humor. In the center is a mosaic of Medusa, the mythological woman whose gaze could turn anyone into stone. Around her stand stone sculptures and representations of spirited women: Artemis, goddess of the hunt, and fertility; Persephone, goddess of fashion; and the eight maenads, worshippers of Bacchus, dancing in ecstatic frenzy.

In the Spanish Cloister adjacent to the courtyard hangs the remarkable El Jaleo, by John Singer Sargent. This sizable painting, 232 cm x 348 cm, reflects Mrs. Gardner’s joy in physical movement, and unbridled activity. Sargent “named the painting El Jaleo to suggest the name of a dance, the jaleo de jerez, while counting on the broader meaning jaleo, which means ruckus or hubbub.”[26] Mrs. Gardner acquired this painting through perseverance and patience. Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, the brother-in-law of Julia [Gardner] Coolidge, owned El Jaleo, and in time simply gave it to Isabella. Coolidge is also the man who wrote: “I think you ought to turn Catholic. I think I should immediately turn priest to hear your confessions.”[27]

Another work, a fresco of Hercules by Piero della Francesca, further defines Mrs. Gardner’s presence. A young Hercules, almost nude, stands boldly with club (a baseball bat?) in hand. It was no secret that Mrs. Gardner delighted in the appearance of well built, handsome young men. Once again, perseverance and patience brought this work into the museum as she conducted nearly five years of negotiation and made payment of substantial import duties. She liked to win.

Isabella Stewart Gardner “probably would have understood John Updike’s comparison of Ted Williams to Achilles…She might even have seen the bat and glove of baseball (as others have) the lance and chalice of the Grail quest.”[28] She willingly and zealously challenged social norms, leaving fodder for the gossips of Boston and beyond. Her museum, called eclectic by some, truly represents a unique woman who engaged in a competition with anyone – chiefly men – who dared to face her. She displayed a courage and empathy that allowed her to secure what she wanted, a museum, and to support those for whom she cared, and to whom she remained forever loyal.

In 2013, after the Boston Red Sox had won Major League Baseball’s World Series, the Gardner Museum displayed a large banner proclaiming “Oh You Red Sox.” This was not only a gesture to praise the Red Sox, but also a means to celebrate the life of Isabella Stewart Gardner, art collector, mentor, muse and Red Sox fan. Her legacy as a Red Sox fan endures as visitors sporting Boston Red Sox clothing or paraphernalia receive $2.00 off admission to the Gardner Museum.

____________

[1] Louise Hall Tharp, Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner (New York: Little, Brown, 1965), 290

[2] Bill Nowlin, “The Boston Americans Never Existed,” Baseball Almanac, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/articles/boston_pilgrims_story.shtml

[3] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 15

[4] George L. Watson, “Isabella Stewart Gardner,” in Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Vol. 1, ed. Edward T. James et al. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 16-17.

[5] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 74

[6] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 171

[7] Morris Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1925), 31.

[8]Wanda M. Corn, “Art Matronage in Post-Victorian America,” Cultural Leadership in America: Art Matronage and Patronage, Fenway Court 27 (1995): 86

[9] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner,

[10] Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Art of Scandal: The Life and Times of Isabella Stewart Gardner (New York: Harper Collins, 1997), 182

[11] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner, 120

[12] Tucci, The Art of Scandal,104

[13] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 104-105

[14] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 153

[15] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 187

[16]Joshua Glenn, “The Rooter,” Boston.com Sports, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/articles/2005/02/27/the_rooter/

[17] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 289-290

[18] Tharp, Mrs. Jack, 149

[19] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 284

[20] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 284

[21] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner, 90

[22] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner, 220

[23] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner, 12

[24] Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner, 13

[25] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 251

[26]Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.gardnermuseum.org/collection/artwork/1st_floor/spanish_cloister/el_jaleo

[27] Tharp, Mrs. Jack,184

[28] Tucci, The Art of Scandal, 105